Long-line fishing in the Galapagos Archipelago

Despite being banned in the Galapagos Islands since 2008, a discussion has resumed on the use of long-line fishing in the Archipelago. But, the consideration has raised concern due to the environmental impact that long-line fishing has on marine ecosystems and endangered species.

Despite being banned in Galapagos since 2008, a discussion has resumed on the use of long-line fishing in the Archipelago. In 2017, as part of a trade-off deal for the declaration of a no-take sanctuary in the northern third of the marine reserve, a new experimental longline fishery was authorized. The first phase was completed in 2018 but was not continued, due to lack of funding. Now, under the need to reactivate an economy that has been devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic, a small but vocal group of fishermen has convinced the Galapagos authorities to request that the next phase be implemented.

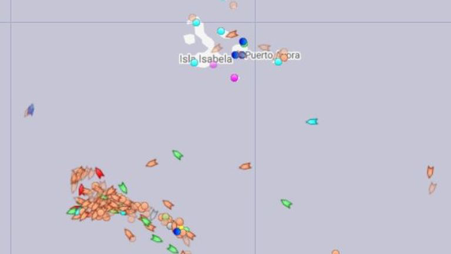

The consideration has raised concern due to the environmental impact that long-line fishing has on marine ecosystems and endangered species. The request has been denied in the past by the Junta Ciudadana Provincial deGalápagos – a provincial citizens board. However, it is now being welcomed. Furthermore, this turnaround in opinion comes at a challenging time. A fleet of around 260 industrial fishing boats has been stationed in international waters on the edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone, and Ecuador’s national fleet of industrial purse seiners and semi-industrial longliners continually ply the waters just outside the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) boundaries, putting extra pressure on the precious marine resources of the Islands.

What is long-line fishing?

Long-line fishing is a technique used to catch fish in open water. It involves a main float line which is strung out across vast distances up to 100 km. Then secondary vertical lines are attached at regular intervals with baited hooks. A 100 km line can have roughly 3000 hooks. These long-lines are used near the surface to catch open-water fish like tuna, or near the seafloor to catch bottom-dwelling fish. Longline fishing has been a source of controversy in Galapagos ever since the creation of the marine reserve in 1998, and it continues to occur illegally. In this current experimental fishery, fifteen local vessels took part in the first phase, using 50-hook vertical and horizontal longline arrangements.

How is long-line fishing damaging?

The major concern is that modern long-line fishing equipment is very efficient and highly non-selective. The catching of a non-target species is called ‘by-catch’. By-catch often consists of vulnerable or endangered species which are attracted to the bait and can get caught on the lines as they swallow the hook or become tangled, suffering significantly. Sharks, which need to keep swimming to allow oxygen to pass over their gills, can suffocate on the lines. Other animals, such as sea turtles and birds, can end up drowning. Long-lines are often left for up to 24 hours and can take at least a day to be hauled in.

Roughly, 300,000 sea birds are estimated to die on long-lines globally each year. Albatrosses are especially at risk; it is believed that four albatrosses drown per 100,000 lines set, which is about 400 birds a week. Currently, 19 of the world’s 22 albatross species are threatened with extinction, including the waved albatross which is found across the Galapagos Archipelago.

How does this affect Galapagos?

On average, long-lines consist of about 35% of non-target species, but it is thought that by-catch can represent up to 90% of the catches in ecosystems like Galapagos.

A recent study analysed data from a 2012-2013 long-line fishing project in Galapagos. A total of 4,895 animals from 33 species were captured from 12 vessels. Of those, 16 species were protected megafauna including; Galapagos sharks, blacktip sharks, oceanic manta rays, scalloped hammerhead sharks, thresher sharks, silky sharks, Galapagos green sea turtles, Galapagos sea lions and Galapagos fur seals.

The biggest threat of long-line fishing in Galapagos is to sharks, which are already being targeted for their fins. In 2017, a Chinese fishing vessel Fu Yuan Leng 999 was intercepted in the GMR by Galapagos National Park (GNP) rangers and members of the Ecuadorian Navy. The boat had more than 6,000 dead sharks on board. In addition, in May this year, 26 tonnes of shark fins were seized by Hong Kong customs officials inside two shipping containers from Ecuador worth US$ 1.1 million.

The GNP estimates that if long-line fishing is reinstated in the GMR, over 10,000 sharks will be caught annually.

However, a secondary threat is the need for large quantities of bait. These are usually mullet or other similar fish that are caught in coastal bays using nets. If used in shark nursery grounds, this can have a serious impact on their early life stages.

What is currently happening in Galapagos?

The Ecuadorian government has been monitoring an international industrial fishing fleet, which has been stationed just outside the Exclusive Economic Zone in a narrow band of international open water. These fishing vessels are not illegal as they sit just outside the protected waters of the GMR. Find out more.

Back in June, the Ministry of Production and Fisheries in Ecuador announced a multi-pronged approach to protect sharks, a result which GCT’s project partner, Dr Alex Hearn, played an integral role in. They stated that “Ecuador condemns any act related to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, especially when these acts are linked to such a sensitive and important species in marine ecosystems as the shark” and that the sale and export of five new shark species will be prohibited.

This announcement came a few weeks after a proposed protected swimway between Galapagos and Cocos Island, Costa Rica, was declared a Hope Spot. Since then, the Galapagos Marine Reserve has also been declared a Hope Spot. We have been supporting the proposed swimway since 2018; helping our science partners gather essential evidence needed to drive forward the creation of this 240,000 km2 route. The swimway is critical for protecting endangered Galapagos marine species.

What are we doing?

As part of our Endangered Sharks of Galapagos programme, we are:

- Building upon the research already undertaken to improve our understanding of whale shark migratory movements, as well as other open ocean, migratory species.

- Using this evidence to create the world’s first protected ‘swimway’ between Galapagos and Cocos Island National Park in Costa Rica.

- Enhancing protections for shark nursery grounds within the GMR.

How can you help?

Please help us conserve the endangered sharks of Galapagos today by donating to GCT, adopting a hammerhead shark or becoming a GCT member.

Related articles

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

Global relevance: COVID-19 and sea cucumbers