Sharks: Our ocean’s superheroes, not villains

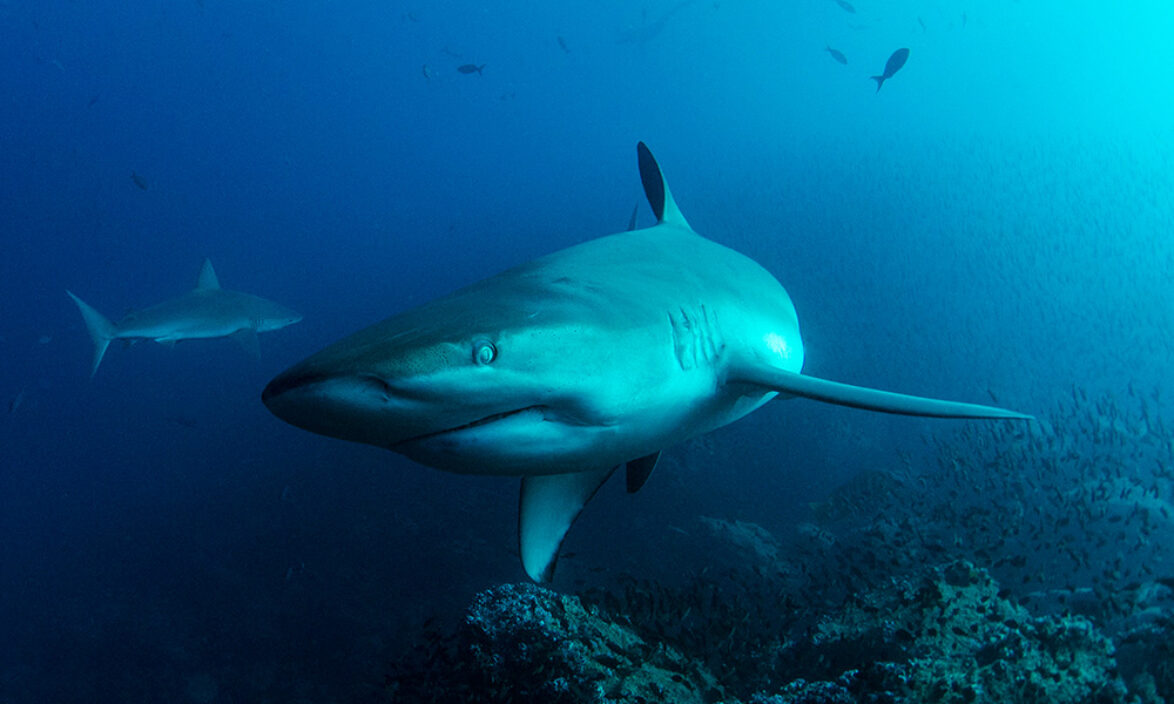

While sharks may appear scary to some, the majority of shark species pose no threat to humans, and we ignore their vital role in our marine ecosystems at our peril.

Those first two notes of the Jaws opening sequence still fill many of us with dread and fear. Released in 1975, no one could have predicted the film’s impact on sharks for decades to come.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species, more than one third of all shark species are threatened with extinction, a shocking statistic that some believe is in part influenced by Steven Spielberg’s iconic film.

The sad reality is that sharks face many threats at all stages of their life. Climate change and plastic pollution are having devastating effects on shark habitats, including mangroves which provide critical nursery grounds for many species, such as the Vulnerable blacktip shark. Out on the open ocean, overfishing, the trade in shark fins and bycatch (the unintentional capture of a species while fishing for other species) decimate populations that then struggle to recover due to their slow reproductive rates.

If sharks were to go extinct, this would have disastrous knock-on effects on our oceans due to their critical role in protecting our marine ecosystems.

Why sharks matter

Sharks play a vital role in marine ecosystems; they help maintain the delicate balance of marine life, keeping our oceans healthy.

Sharks are apex predators, meaning they sit at the top of a food chain with no or very few natural predators of their own. Apex predators keep food webs in balance and encourage high levels of biodiversity by feeding on abundant prey species, which, if left unchecked, can outcompete less abundant species, leading to biodiversity loss. They also remove weak and sick prey individuals, which keeps prey populations healthy.

Large-bodied predators such as sharks also play a critical role in regulating our climate through their role in sequestering ‘blue carbon’ (carbon captured from the atmosphere and stored in the ocean). Coastal shark species protect critical blue carbon sinks, including seagrass meadows and kelp forests, by predating on species that graze on these sinks. Sharks are also carbon sinks themselves. When a shark dies naturally and falls to the ocean floor, the carbon held in their body is sequestered into the sediment and prevented from being released into the atmosphere, where it can contribute to changes in our Earth’s climate.

The sharks of Galapagos

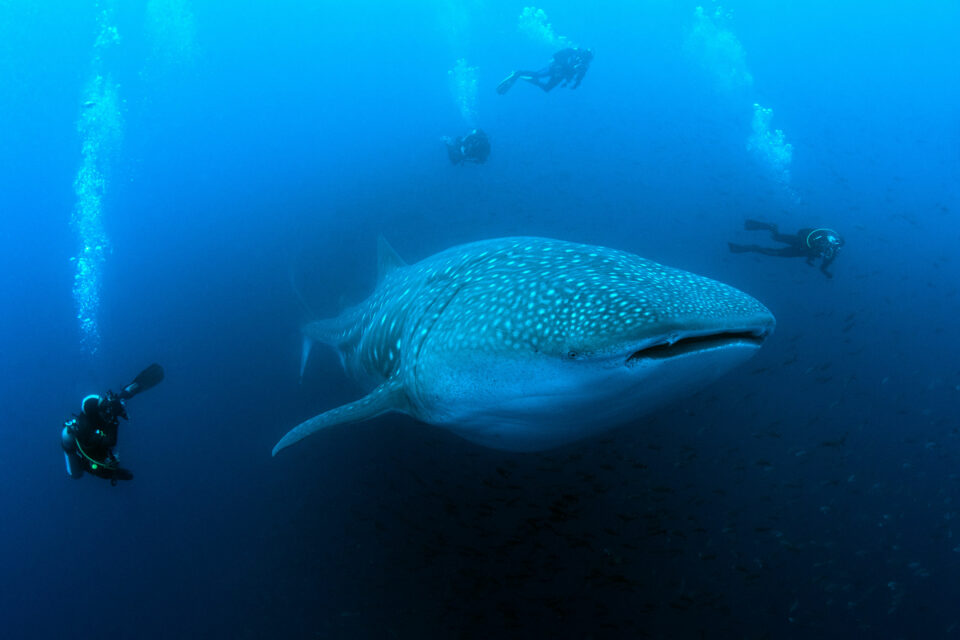

At least 33 species of shark have been recorded in the nutrient-rich waters around the Galapagos Islands, although scientists believe there are more species to be discovered. Some of the most iconic species include the Endangered whale shark, the world’s largest species of shark, most commonly seen close to the islands of Wolf and Darwin. Galapagos is one of the few places on Earth where Critically Endangered scalloped hammerhead sharks can be seen gathering in large schools of up to several hundred.

Many of the threats facing sharks around the world are also seen in Galapagos waters. Despite the establishment of the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) in 1998 and the Hermandad Reserve in 2022, which increased Ecuador’s protected waters from 13% to 18.9%, sharks continue to be targeted by commercial and illegal fisheries or accidentally caught, injured or killed as bycatch by trawls, purse-seine nets, gillnets and longlines.

That’s one of the things I still fear—not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me for the feeding frenzy of crazy sport fishermen that happened after 1975

Protecting the sharks of Galapagos

This is a critical time for sharks across Galapagos, which is why we need management strategies that ensure protection for these species throughout their lifetime.

Often located in shallow waters surrounded by mangroves, shark nurseries provide a safe place for young sharks, including bullhead and whitetip reef sharks, to grow up. Exciting news came earlier this year after shark and ray nursery sites in Galapagos, including off the island of San Cristobal, were identified by the IUCN’s Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRA) project as priority areas for shark and ray conservation management due to their critical role in ensuring the long-term survival of species. The nursery sites are some of the first in the world to be included in the project’s electronic atlas, showcasing worldwide nursery sites that require enhanced protection. For scientists in Galapagos, this decision will hopefully support future environmental impact assessments of activities affecting shark conservation and help build the case for stronger protections.

For many shark species, the open waters of the Galapagos Marine Reserve are an essential part of their migratory routes. Recent research has shown that some migratory sharks, including whale sharks, often move between the GMR and Cocos Island National Park (CINP) in Costa Rica. Once these sharks move outside of the protected waters of the GMR, they are extremely vulnerable to industrial fishing. The Endangered Sharks of Galapagos and Galapagos Whale Shark projects, supported by GCT, are using the latest technology to tag and track migratory species to improve our understanding of shark migratory movements. They are using the data gathered as evidence to create the world’s first protected ‘swimway’ between Galapagos and Cocos Island National Park in Costa Rica.

While countries are conscious of their national ocean boundaries, migratory marine species are not and are free to move as they please, posing a challenge for conservationists. Protecting migratory species, including sharks, in open ocean areas beyond national jurisdictions has been a high priority for many years. Earlier this year, we saw a crucial breakthrough at the United Nations, as nations finally agreed, after almost 20 years of talks, on a High Seas Treaty, which will put mechanisms in place to create Marine Protected Areas in parts of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction. This is a crucial step towards the shared global goal of protecting 30% of our oceans by 2030.

While sharks may appear scary to some, the majority of shark species pose no threat to humans, and we ignore their vital role in our marine ecosystems at our peril. To protect these iconic creatures, we need a holistic view of how we’re addressing threats, since issues such as climate change, pollution and overfishing all interact with each other. These are threats sharks face at every stage of their life, meaning conservation efforts must span their entire lifecycle – the health of our oceans depends on it.

The bay swarmed with animals; fish, shark & turtles were popping their heads up in all parts.

How you can help

Ocean Protection Appeal

Related articles

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

World Oceans Day 2022: Tagging Ocean Giants