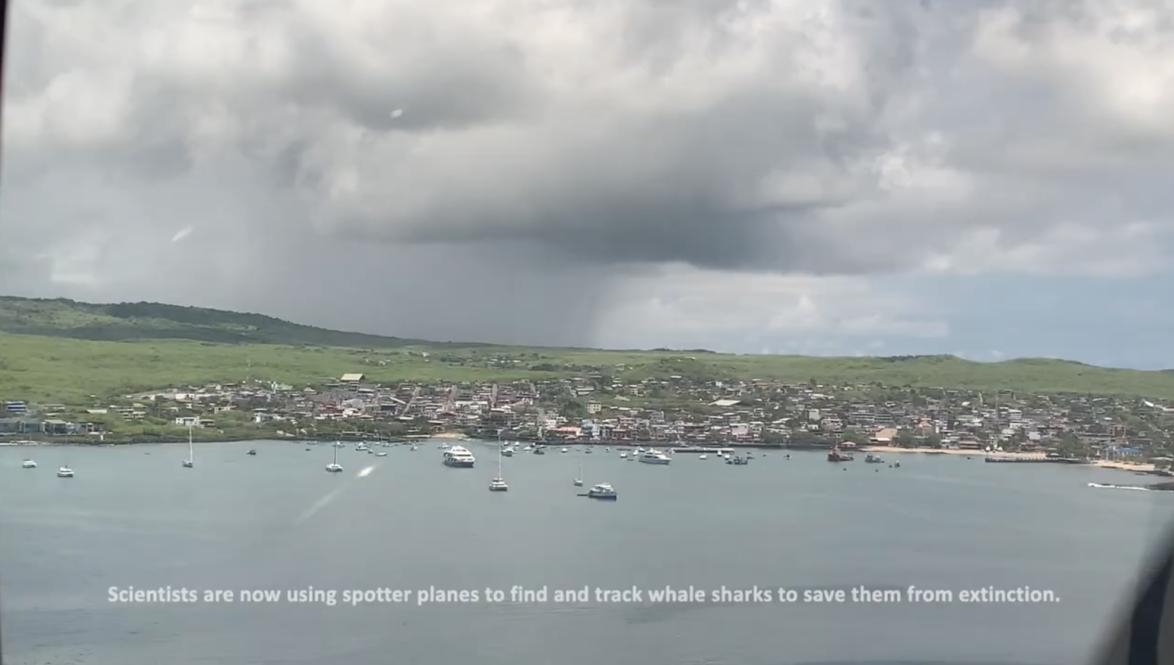

Scientists use ultra-light aircraft to tag and track whale sharks off the southern Galapagos islands for the first time

A multi-institutional team of scientists has recently concluded a ground-breaking research expedition to tag and track whale sharks, and other key migratory marine species, in the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

Scientists from the Galapagos Science Center (Universidad San Francisco de Quito), Georgia Aquarium, MigraMar, the Galapagos Whale Shark Project and the Galapagos National Park Directorate took part in the expedition, which was supported by Galapagos Conservation Trust, Rufford Foundation, PADI Foundation and the Royal Society.

Working onboard the local fishing vessel Yualka II over a two-week period, they placed satellite tags on scalloped hammerhead and blue sharks and yellowfin tuna, as part of a larger study to establish their movement patterns and the role of marine protected areas in their conservation.

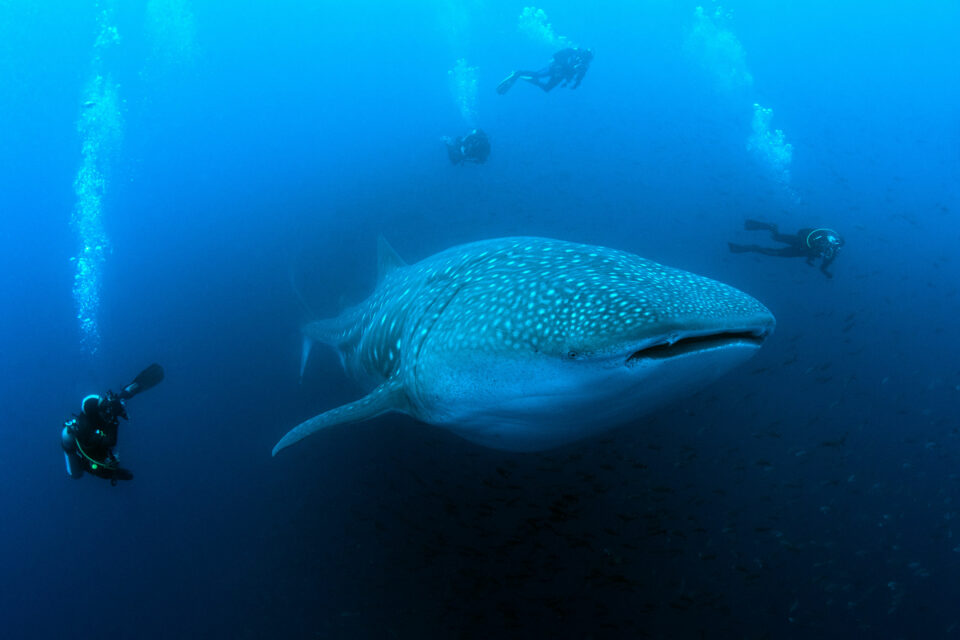

However, the main target of the trip was to find the elusive whale sharks. Galapagos is globally renowned for its aggregation of large female whale sharks at the northernmost Darwin island from June through November. “We’ve been tracking the sharks there for a decade,” said Sofía Green, a researcher with the Galapagos Whale Shark Project and MigraMar. “They tend to spend only a day or two at Darwin, before heading out west into the open ocean, and then turning around and travelling to the shelf break of Ecuador and northern Peru at the end of the year. But where are they before they arrive at Darwin?”

Whale sharks are reported around the southern islands early in the year, leading the team to speculate that this area is part of a migratory loop, with the sharks moving up through the Archipelago as the year progresses. “We had a big breakthrough in 2017, when our pilots discovered 15 whale sharks close to the surface while on an aerial patrol to the south of Isabela,” said Harry Reyes, Head of Ecosystems at the Galapagos National Park Directorate. The researchers were able to team up with Julio Vizuete, from ‘Ecuador Bajo Mis Alas’ (Ecuador Under My Wings), and use his ultralight airplane to search for whale sharks around the southern islands and seamounts.

On the first day of the expedition, the team encountered a whale shark at a seamount not far from San Cristobal. “She was close to the surface, so we were able to tag her and take swabs from her skin and around her gills, as part of a wider study to understand how their microbiome changes in different environments,” said Cameron Perry, a PhD student at Georgia Aquarium and Georgia Institute of Technology.

With aerial support, the team had a further nine whale shark encounters and were able to place five satellite tags, all on large females. “Whale sharks are mostly solitary, and when they form feeding aggregations at coastal locations, these are dominated by smaller individuals. Offshore locations are challenging to study, but we’ve been supporting work here in Galapagos and at other offshore islands such as St. Helena in the Atlantic, for several years. This is where we find adults, and in particular in Galapagos, large females. I would not be surprised if the females we tagged on this trip eventually made their way up to Darwin later in the year. We are hopefully a step nearer to identifying the full migratory loop,” explained Dr. Kady Lyons, Research Scientist at Georgia Aquarium.

The expedition is the first step in a wider project with Universidad San Francisco de Quito and partners to monitor and track marine megafauna from the air in the Galapagos Marine Reserve and along the coastal waters of mainland Ecuador.

Adapted from a joint press release on 25/04/2022

I would not be surprised if the females we tagged on this trip eventually made their way up to Darwin later in the year. We are hopefully a step nearer to identifying the full migratory loop.

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks