Vampire finches: how little birds in Galapagos evolved to drink blood

For most people, the word “vampire” brings to mind Dracula or perhaps slayers such as Blade or Buffy; or maybe even the vampire bats of South America. Few will think of a small and rather lovely bird – the finch.

Kiyoko Gotanda, University of Cambridge; Daniel Baldassarre, State University of New York Oswego, and Jaime Chaves, San Francisco State University

© Jaime Chaves

For most people, the word ‘vampire’ brings to mind Dracula or perhaps slayers such as Blade or Buffy; or maybe even the vampire bats of South America. Few will think of a small and rather lovely bird – the finch.

But there are indeed ‘vampire finches’ that feast on the blood of much larger birds, and they were introduced to the world in a fantastic segment of Perfect Planet, the new series narrated by David Attenborough for the BBC. For us, these finches needed no introduction as we have studied them closely.

These birds are found on the Galapagos Islands, a volcanic archipelago located about 1,000 km (600 miles) off the coast of Ecuador. The Islands are a biodiversity hotspot in part because of their isolation. Organisms that somehow make it to Galapagos must adapt to the harsh conditions or go extinct.

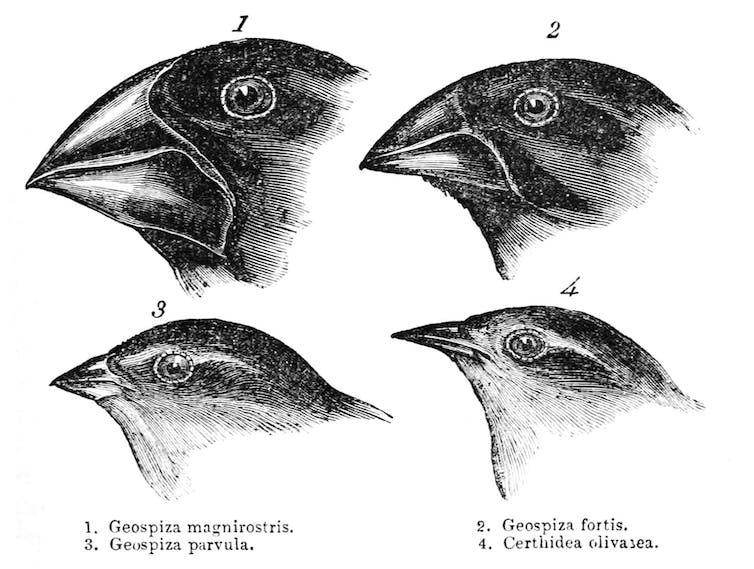

One such group of organisms is the Darwin’s finches. Named after the naturalist Charles Darwin, who collected examples on his famous voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, this group of finches consists of several species that have evolved from a common ancestor. Each species has evolved a different bill size and shape which allows it to exploit different food items. For example, the cactus finch has a long thin bill that allows it to consume the nectar of cactus flowers. Some species have bills that are better at crushing seeds, while others are better at consuming insects or plants.

It makes sense that different species of finches evolved to feed on different types of food items on Galapagos, but where did blood-feeding come from?

How blood-sucking evolved

The vampire finches are found only on Wolf and Darwin, the two northernmost islands of the Archipelago and remote even by Galapagos standards. Both islands are tiny, each less than a square mile, and are separated from the larger islands by 100 miles of open ocean. Freshwater is extremely rare and some food can disappear entirely during the dry season.

At some point in the last half-million years – recent in evolutionary terms – finches arrived on Wolf and Darwin and began to co-exist with large seabirds which nest on the islands, such as red-footed and Nazca boobies. Over time, it seems the finches likely evolved to eat parasites found in the feathers and on the skin of the boobies. This was ‘mutualism’ in action: the boobies benefited from parasite removal, and the finches benefited by having an alternative to their usual diet of nectar, seeds and insects which can disappear during the dry season.

Eventually however, the removal of parasites led to open skin lesions on the boobies, allowing the finches to consume blood. The finches even learned to pierce skin at the base of young feathers to access the blood directly, no longer needing the insect parasites anymore. Thus, the finches capitalised on an alternative food resource, blood from the boobies, and earned themselves the nickname ‘vampire finches’.

It’s hard to know exactly how much of the finch’s diet is booby blood, but our unpublished data suggests it’s about a tenth. Natural selection appears to have fine-tuned the vampire finch beak for skin-piercing and blood-sucking, as the birds have evolved particularly long and pointy beaks compared to non-blood-feeding populations on other islands. And once a blood-feeder pierces the skin, it still needs a way to consume and digest the blood. When we studied the microbes found in the guts of these vampire finches in search of adaptations we found a very different microbiome from any other species of Darwin’s finches, presumably caused by the blood diet.

What it’s like to see in person

Two of us, Daniel and Jaime, visited Darwin and Wolf to study these fascinating finches on islands that are very rarely visited, even by researchers. Getting there was extremely challenging as there are no beaches for landing a boat. We had to approach the cliffs in a small dinghy and then wait for a brief gap in the waves before jumping onto sharp, black lava rocks. But this isolation means the vampire finches are plentiful, and the dense breeding colonies of boobies made it easy to envision how this strange blood-sucking behaviour could have evolved.

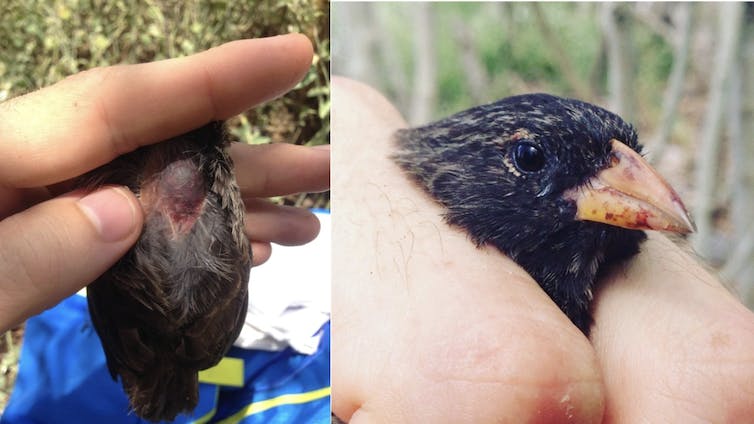

Left: a vampire finch crop (food store in the throat) full of blood. Right: A vampire finch with bloody bill © Daniel Baldassarre

The boobies are incredibly vulnerable when tending to nests and chicks, as they are reluctant to abandon them, even temporarily. We observed scores of vampire finches clamouring all over the backs, tails, and wings of boobies, opening up substantial wounds with their sharp beaks, and drinking their fill of blood. Interestingly, the finches seem to act like a true parasite, inflicting enough damage to secure a meal without excessively harming the host.

For the boobies, the whole experience really is very similar to a human being attacked by mosquitos. Though they can tolerate the finches, the small bloodsuckers are a nuisance that the boobies do try to get rid of. And when it all gets too much, they can be forced to fly away.

And who can blame them? When we captured finches to collect samples, we found gullets full of blood, and beaks stained red. It was evident that the little vampires were not merely lapping up a few drops of blood.![]()

Kiyoko Gotanda, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Université de Sherbrooke and, University of Cambridge; Daniel Baldassarre, Assistant Professor of Zoology, State University of New York Oswego, and Jaime Chaves, Assistant Professor, Ecology and Evolution, San Francisco State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here. GCT is not responsible for external content.

Related articles

Double your donation to rewild Galapagos with the Big Give

Promising signs on Floreana as five species of finch are released