Meet the six Galapagos species you can adopt with GCT

One of the ways we encourage people to support the wildlife of Galapagos is through our species adoptions, which help fund several projects across the Archipelago.

While the Galapagos Archipelago is one of the most pristine places on Earth, it is also suffering from the negative impacts of human activity. On the Islands, invasive species are pushing some species to the brink of extinction, while plastic pollution poses an increasing threat in the marine environment. It can be hard to know how to help from the other side of the world.

One of the ways we encourage people to support the wildlife of Galapagos is through our species adoptions, which help fund several projects across the Archipelago. In this blog, we will introduce you to six of the Archipelago’s most famous residents, which, despite being favourites amongst the tourists and residents of Galapagos, need your help.

The Galapagos Islands are teeming with life, making this one of the most ecologically important places on earth, and yet without our help many of the species we love may be lost forever.

Introducing the gentle giant of the seas

The whale shark is the largest species of shark and the largest fish alive today. It is a migratory species, with the Galapagos Islands being just one of many stops on their long journey in search of food and mates.

In Galapagos, 90% of the whale sharks seen appear to be pregnant females. Some scientists believe females come to the Islands to give birth. Research led by the Galapagos Whale Shark Project is currently underway to discover if this is the case.

Whale sharks are typically grey to blue with white spot patterns, which, just like the human fingerprint, are unique to each shark, making it easy to identify and track individuals as they navigate often dangerous waters where they may encounter commercial fisheries and marine plastic pollution.

By tracking the movements of migratory marine species, including whale sharks, the Endangered Sharks of Galapagos Programme aims to provide the research needed to support the Ecuadorian government in protecting at least 30% of its waters by 2030.

Adopt a whale shark

By adopting a whale shark today, you can learn about this magnificent but enigmatic animal, whilst protecting them and other Galapagos species.

Take a step back in time to meet a historic species

With a lifespan of over 100 years, giant tortoises have stood the test of time. Arriving from mainland South America 2-3 million years ago, the species underwent diversification into 15 species, which differed in physical appearance and distribution. Today, however, only 12 species are thought to be still extant.

Giant tortoises spend up to 16 hours a day resting and the remaining hours eating grasses, fruits and cactus pads. The breeding season occurs between January and May, with females laying up to 16 eggs, each the size of a tennis ball. After 130 days, the eggs, which have been incubated by the sun, hatch and the young tortoises set off on their own.

During Charles Darwin’s visit to the Islands, giant tortoises provided a fresh source of meat which could be kept alive with minimal effort. This discovery proved disastrous for tortoise populations, with a loss of between 100,000 and 200,000 individuals.

Today, human activity, including the introduction of invasive species such as dogs and rats, which predate tortoise eggs, and the development of migration barriers, including roads and fencing, pose severe threats to tortoises. Plastic pollution has also recently emerged as a threat, with new research revealing that giant tortoises on Santa Cruz island are ingesting litter, including medical face masks, glass and plastic bags.

Luckily, the Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Project is helping to mitigate these threats by determining tortoises’ spatial needs, assessing changes in populations over time, and looking at the extent to which their health is being impacted by human activity.

Adopt a Galapagos tortoise

By adopting a Galapagos giant tortoise today you can help to protect this species, their habitats and other Galapagos wildlife.

Dive beneath the waves to meet a curious creature

The Galapagos Islands are one of the best places in the world to see scalloped hammerhead sharks, which gather in schools of up to several hundred. They are named after the ‘scalloped’ front edge of their hammer-shaped head, which has evolved to provide exceptional vision and is filled with sensory cells that help sharks detect the electric fields given off by their prey, which includes stingrays, squid and schooling fish.

After a 9-12 month gestation, females give birth to live young, who spend several years living in coastal nursery sites to avoid being eaten by other sharks. Following these crucial years within the safety of the nursery, a shark will head out to the open ocean, where they risk being targeted by commercial and illegal fisheries for their fins, as these are highly valued in the Asian market for shark fin soup.

The Endangered Sharks of Galapagos Project is working to ensure that scalloped hammerheads are protected at every stage of their lives. Thanks to this critical data, Galapagos nursery grounds were designated by the IUCN in 2022 as Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRAs), an important first step to conserving vulnerable shark and ray populations and other species that rely on sheltered mangrove lagoons in their life cycle. Amazingly, these ISRAs are among the first to be recognised worldwide.

Adopt a hammerhead shark

By adopting a scalloped hammerhead you can learn more about these fascinating animals, whilst protecting them and other Galapagos species.

Say hello to a favourite amongst visitors to the Islands

Found only on the Galapagos Islands, the Galapagos penguin is one of the smallest penguins in the world. They live mainly on Isabela and Fernandina islands in caves and crevices in the coastal lava. While they spend a lot of their time on land, they are most at home in the water, with their agile bodies reaching speeds of up to 35km an hour when hunting.

A penguin’s breeding success is highly dependent on environmental conditions, making changes in climatic conditions due to El Niño events and climate change a serious threat to the species’ future.

On land, predation is minimal; however, at sea, penguins can be hunted by sharks, fur seals and even sea lions. They are also potentially at risk of being entangled in marine plastic pollution or mistaking it for food. Currently, we are working with partners to assess the risk of marine plastic pollution to Galapagos penguins as part of our Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos programme.

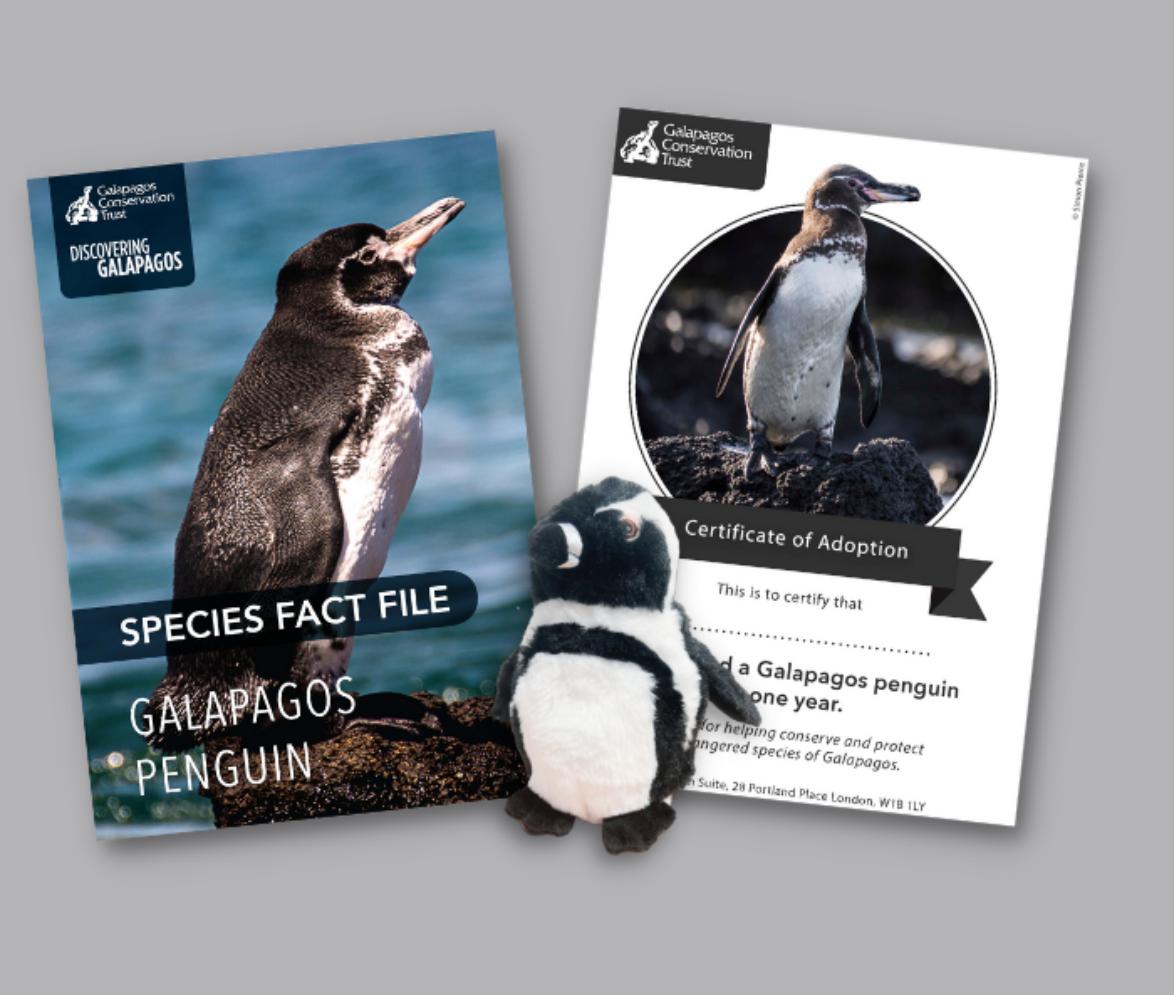

Adopt a Galapagos penguin

By adopting a Galapagos penguin today, you can help to protect this species and other wildlife on the Islands.

Introducing a very playful pal

Despite its name, the Galapagos sea lion is not found exclusively in the Galapagos Islands but can also be found on Isla de la Plata, just off mainland Ecuador. While they spend significant time resting along beaches, their streamlined bodies make them highly adept at hunting in the water, diving to depths of almost 600m to feed on schools of sardines.

Sea lions are playful and inquisitive, making them a favourite among tourists. However, during the breeding season, males become highly territorial as they compete for females. Pups form a strong bond with their mother for the first week, developing a unique call that distinguishes them from other pups. Once a pup reaches 11–12 months old, they will leave their mother to begin their adult life.

Research by the Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos programme recorded 38 Galapagos species, including the Galapagos sea lion, entangled by or having ingested plastic, highlighting just how pervasive the issue is across the Archipelago.

By bringing together an alliance of NGOs, community groups and scientists, this flagship programme is combining ground-breaking scientific research with coordinated education and outreach to make Galapagos plastic pollution free once again.

Adopt a sea lion

By adopting a curious and charismatic sea lion today, you can learn about this animal whilst protecting them and other Galapagos species.

Meet a tiny but mighty Galapagos resident

Known to be highly inquisitive, the Floreana mockingbird is almost identical to the Galapagos mockingbird except for its red-brown eyes and dark patches on the side of its breast.

During Charles Dariwn’s voyage to the Galapagos Islands, he noted the abundance of the species across Floreana island. Little did he know that only 50 years after his expedition, the species would become extinct on the island due to habitat loss and predation from invasive species.

Today, the Floreana mockingbird can only be found on two tiny islands off the coast of Floreana, with the overall population consisting of several hundred individuals.

By protecting the small population remaining on the two islets, the Floreana Mockingbird Project aims to bring the species back to its original home. This is part of the wider Restoring Floreana programme which is focused on eradicating invasive species across the island to ensure the Floreana mockingbird and 11 other locally extinct species will survive and thrive once reintroduced.

Adopt a Floreana mockingbird

By adopting an inquisitive mockingbird today, you can learn about this animal whilst supporting projects that are securing the species’ future.

The Galapagos Islands are teeming with life, making this one of the most ecologically important places on earth, and yet, without our help, many of the species we love may be lost forever. Adopting an animal is a small yet powerful way to help secure a safe future for the Islands and the many species that call them home.

Check out our GCT shop

100% of our shop’s profits go towards funding vital conservation work in the Galapagos Islands. We ship worldwide in recyclable, plastic-free packaging.

Related articles

5 of the most colourful birds in Galapagos

10 year anniversary of the death of Lonesome George