How technology is changing conservation in Galapagos

From unmanned drones and acoustic sensors to remarkable advances in artificial intelligence, new technologies are playing a key role in the conservation of the Galapagos Islands.

When Charles Darwin made his history-shaping visit to the Galapagos Islands in 1835, he arrived on a ship packed with the latest technology. The HMS Beagle, just 90 feet from prow to stern, carried chronometers, barometers, theodolites and microscopes, along with a library stocked with some 400 volumes, where Darwin slept in a hammock strung across the drafting table.

While many of the Islands look much the same today as they would have in Darwin’s time, the technology available to scientists working in Galapagos has evolved in ways that would have been almost unimaginable to the great naturalist. Satellites orbiting the Earth allow not just the navigation of ships, but the real-time tracking of individual animals on land and in the ocean; unmanned drones can map coastlines and create 3D terrain models accurate to the nearest centimetre; advances in genetics mean we can detect the presence of species from trace levels of their DNA in water or soil; and recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence promise to transform the ways in which data are collected, analysed and utilised to inform conservation strategies and protect threatened habitats.

Monitoring wildlife in remote areas

Researchers and conservationists working in Galapagos face a number of challenges when gathering data. Much of the terrain is rocky and inhospitable, coastlines are difficult to land on, and there are no roads or other infrastructure in National Park areas reserved for wildlife. Minimising the disturbance to fragile habitats is also a key consideration. Outside the populated areas, internet and mobile phone coverage ranges from patchy to non-existent. Suitable vessels for research trips can be hard to find, and many marine species travel huge distances, far beyond the limits of the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

These challenges are not unique to Galapagos, of course, and remote monitoring of wildlife is nothing new. The American congressman George Shiras III is credited with inventing the first ever camera trap in the 1890s, a simple device with a tripwire which triggered a camera and flash. Today’s camera traps are much less intrusive, using infra-red to detect movement, and are widely used in Galapagos to track both endemic wildlife and invasive species such as rats. Camera traps can provide us with data on the movements and behaviours of wildlife, and how species are interacting, both with other wildlife and with humans.

In recent years, there has also been a rapid increase in the popularity of acoustic monitoring as a tool for conservation. Technological advances mean that acoustic sensors are increasingly affordable, and like camera traps, they are non-invasive and can be left in situ for weeks or months. Even the smartphone in your pocket can now record and identify birdsong, opening up exciting possibilities for citizen science. Like camera traps, acoustic sensors allow us to estimate population density, behavioural trends and disturbance to wildlife from human activity. In Galapagos, this technology has been used to monitor the success of species introductions, such as on Pinzon island where our partners are working to re-establish the locally extinct woodpecker finch.

Even the smartphone in your pocket can now record and identify birdsong, opening up exciting possibilities for citizen science.

However, there are challenges to the use of camera traps and other remote monitoring equipment, particularly in an environment like Galapagos. Up until now, camera trapping has relied on someone physically collecting the data from each camera, which used to mean a roll of film, and nowadays means retrieving a memory card.

One of the most exciting new developments in conservation technology is the possibility of deploying networked sensors, which means that camera traps, acoustic recorders and other hardware can connect online via WiFi, cellular networks or satellites, allowing real-time monitoring and tracking, and reducing the need to physically maintain these devices in the field. This access to real-time data is a game-changer when it comes to tackling issues like poaching or deforestation, as well as monitoring the presence of invasive species, including in the aftermath of an eradication project such as Floreana.

Satellites and GPS tracking

Like many of the technologies that have revolutionised our lives over the last few decades, the Global Positioning System (GPS) was initially developed for military use by the US Department of Defense. In the 1980s, President Reagan authorised civilian use of GPS, and it is now hard to imagine our lives without satnav and Google Maps. It is unlikely that the scientists and engineers who developed GPS would ever have imagined that it would one day be used to track the progress of Galapagos giant tortoises on their annual migration between highlands and lowlands, trackers carefully glued to each tortoise’s carapace!

Satellite technology is also used by the Galapagos Whale Shark Project, with tags used to track both the horizontal and vertical position of the whale sharks, along with other data, such as the temperature of the water and even video footage taken by ‘fin-cams’. Data collected about the migratory paths of species like whale sharks were instrumental in building the case for the enlargement of the Galapagos Marine Reserve in 2022. Satellites also have a role to play in the enforcement of marine protected areas, allowing authorities to identify illegal vessel activity, while on land they can be used to monitor deforestation, habitat loss and the impacts of climate change.

Drones in Galapagos

The use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), more commonly known as drones, is another game-changing technology that is increasingly being deployed across the Galapagos Archipelago. Drones allow researchers and Galapagos National Park Rangers to survey remote and difficult-to-access locations, whether they’re trying to count marine iguanas or identify coastlines where plastic pollution is accumulating. Drones can also assist in the eradication of invasive species, such as on North Seymour and Mosquera, where drones were used to distribute bait in a successful project which led to both islands being declared free of invasive rodents in 2021.

One of the main barriers to scaling up the use of drones in Galapagos is the lack of local capacity, which is why GCT is working with our partners Conservation International – Ecuador and Airborne Platforms Ltd to train more Galapagos National Park Rangers as drone operators. Internet connectivity has also been a big obstacle, with slow internet speeds preventing the use of cloud-based data solutions. This is now changing, however, with the roll-out of services such as Starlink promising to dramatically improve the capacity for accurate mapping, enable the automation of drone surveys, and speed up the processing of data.

Webinar: Rewilding Floreana

Join us on Thursday 18 April to hear the latest on the restoration of Floreana, with Jeff Dawson of Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust reporting back from his recent trip to the island.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

With so much information being gathered via the tools we have already discussed, conservationists are presented with another challenge: how to process such vast datasets. This is where the recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are opening up exciting new possibilities.

On Floreana, teams have been deploying a new piece of kit called the Sentinel, developed by Conservation X Labs. The Sentinel is a device that plugs into camera traps and uses AI to filter and process images as they are recorded. Highlighted images are sent to users over satellite or cellular networks. Machine learning algorithms can be trained to recognise particular species, meaning the system can be used to alert researchers in near real time to the presence of invasive species. Sentinel models being used in other parts of the world are also able to recognise changes in animal behaviour which could indicate certain diseases.

On Floreana, organisations including our partners at Island Conservation have been using the Sentinels plugged into Reconyx and other camera traps for several months, and the reliability of AI as a tool to share accurate, near real-time updates from the field is promising. Additional features of the Sentinel, such as sending low-resolution images over satellite for human verification, are helping with the use of data from the field to inform rapid decision making.

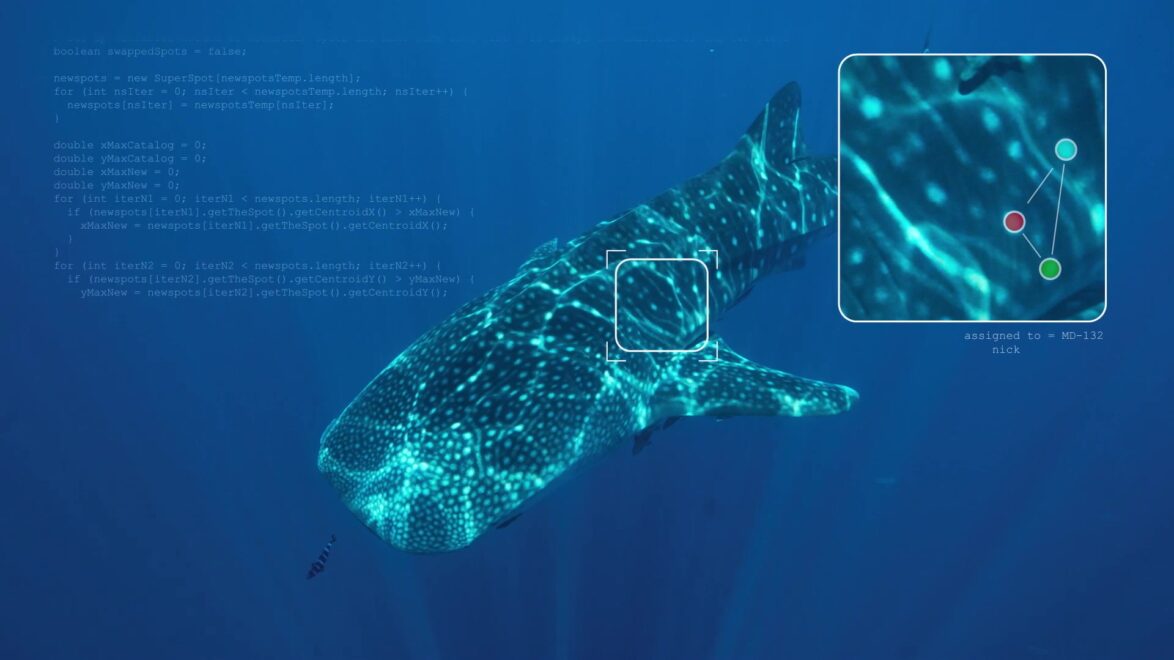

The ability of AI to derive information from photo and video, known as ‘computer vision’, has many valuable applications for conservation. The Galapagos Whale Shark Project (GWSP) is helping to build a global database of individual whale sharks using images both from the project itself and from divers, scientists and amateur photographers around the world, who can upload their whale shark photos via the Sharkbook.ai platform.

An algorithm similar to those used by NASA to track stars is then used to identify individual whale sharks based on their unique pattern of spots, and allows the GWSP team to see where whale sharks go when they leave the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

Researchers at the University of Utrecht, part of our Pacific Plastics: Science to Solutions network, have used machine learning to create a predictive model that identifies the best locations for plastic cleanups, while an initiative called Project CETI is using learnings from large language models (such as ChatGPT) to interpret and potentially translate communication between sperm whales off the Caribbean island of Dominica. This raises the tantalising prospect of interspecies communication, with all the implications that brings.

While there are many challenges to implementing these new technologies – the upfront costs, capacity building, patchy internet coverage, regulations and permits, a lack of agreed technical standards, plus very important considerations about the ethics of technologies such as AI – the potential benefits are huge. Increased collaboration and sharing of information across projects and across disciplines, combined with the ability to analyse huge datasets and respond to threats in real time, will give us a fighting chance as we tackle the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. What’s more, these technologies are already giving us invaluable insights, helping to identify priority areas for protection and equipping authorities to take on the considerable task of policing protected areas on land and at sea.

Machine learning algorithms can be trained to recognise particular species, meaning the system can be used to alert researchers in near real time to the presence of invasive species.

Related articles

Conservation in the digital age – drones in Galapagos

Professionalising the use of drone technology in Galapagos