Galapagos embraces state-of-the-art shark monitoring technology

Drone surveys and remote underwater cameras are changing the way that we monitor endangered shark populations in Galapagos.

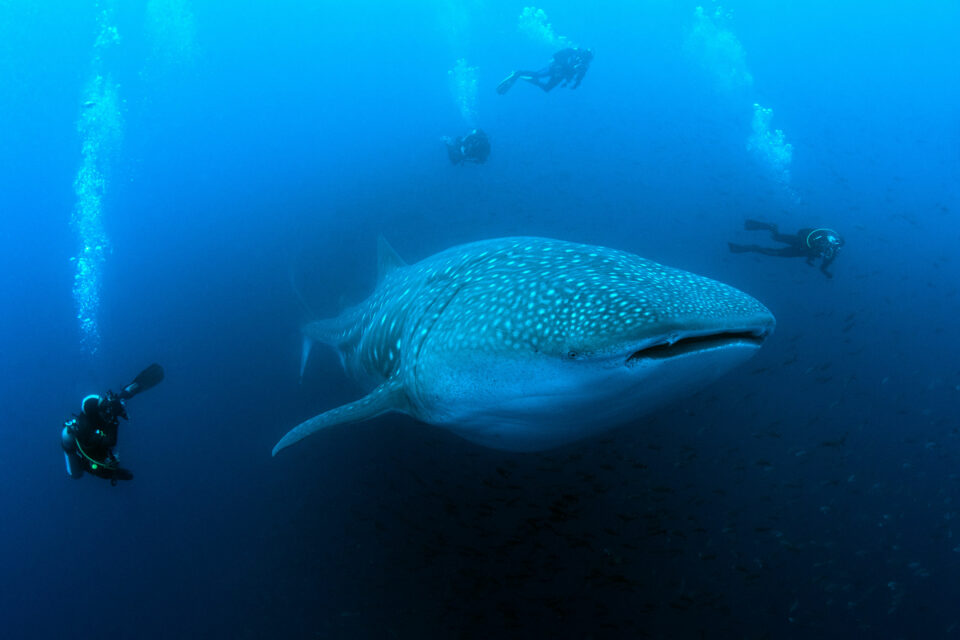

The Galapagos Islands are home to an astounding array of species. The surrounding waters are also home to some of the richest marine ecosystems on the planet, protected by the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) that covers an incredible 133,000km2. From bus-sized whale sharks to small, lesser-known species like the Galapagos bullhead shark, the GMR is famous for its high density of sharks with over 30 species found in it waters.

While sharks in the GMR benefit from full protection and are significantly safer than areas outside its borders, threats such as illegal fishing activity and accidental bycatch remain. Moreover, some shallow mangrove lagoons found around Galapagos’ San Cristobal and Santa Cruz islands are thought to be important nursery sites for species including blacktip and scalloped hammerhead sharks.

In the past year, the GMR has been at the forefront of innovative camera technology designed to monitor shark populations from both the air, via drones, and underwater, via baited remote underwater videos stations (known as BRUVS). Under the umbrella of our Endangered Sharks of Galapagos programme, we have partnered with leading researchers and education specialists to ensure that sharks at all life stages within, and migrating in and out of, the GMR, can be protected.

Earlier this year, researcher Lauren Goodman based at the Galapagos Science Center worked to identify shark nursery sites in the GMR using drone surveys. Drones more accurately and efficiently measure the abundance of juvenile sharks compared to the traditional net surveys, while also being capable of capturing shark presence in multiple types of environments with different environmental conditions.

Juvenile sharks at nursery survey site La Seca © Lauren Goodman

It is important that suspected nursery areas are confirmed as ‘true’ nursery sites, to ensure they receive adequate additional protections from local human activities. Lauren and her team look for sites that have higher numbers of shark pups than nearby areas, provide enhanced growth and survival, and displays of site fidelity as well as consistently using the site.

This year, surveys around the island of San Cristobal have already shown that the suspected sites do indeed have higher numbers of young sharks. We also now have a better understanding of when adult blacktip sharks give birth in Galapagos, with results showing high numbers of newborn sharks in late February and early March. The health of these young sharks was assessed using blood samples, under the supervision of our partner and principle scientist Dr Alex Hearn. Samples will be analysed to help build a picture of the overall health of these young sharks, and answer key questions around their growth and survival at the suspected nursery sites.

In 2020, we will continue regular drone surveys as well as further work on the health of the sharks and monitoring the regularity of human activities, which will ultimately help the Galapagos National Park develop specific, zoned protections at the sites.

Drones are an accurate and efficient way to measure the abundance of juvenile sharks © Alex Hearn

As well as monitoring Galapagos shark populations from the air, during November, marine experts from around the world came together on San Cristobal island to learn more about the use of video technology known as BRUVS. This underwater practice is becoming an increasingly popular method of monitoring marine ecosystems, particularly when studying the size and diversity of shark communities.

The workshop, which was funded in part by our Endangered Sharks of Galapagos Programme, took place at the GAIAS campus of San Francisco University of Quito and the Galapagos Science Center. PhD students Naima Lopez and Christopher Thompson, from the Marine Futures Laboratory at the University of Western Australia, met with the Galapagos National Park Director and partners in the MigraMar Network from around Latin America, to discuss BRUVS monitoring techniques which have the potential to be adopted across the region.

Naima and Christopher have been working on the use of this underwater technology in different parts of the world, under the supervision of Dr. Jessica Meeuwig, who pioneered the technique.

Underwater BRUVS technology is an increasingly popular method of monitoring marine ecosystems © Alex Hearn

Following the workshop, Naima Lopez undertook several days of BRUVS surveys, collecting over 150 datasets from around San Cristobal island in order to build an overview of the local open water fish community. Once this initial dataset is analysed, larger-scale BRUVS work can begin, resulting in the first ever analysis of shark distribution in the GMR, coastal Ecuador and the proposed Galapagos-Cocos ‘Swimway’.

This ‘Swimway’ is a well-known migratory route for sharks leaving the GMR to reach the Cocos Island National Park in Costa Rica. As soon as sharks leave the GMR they are no longer protected against the threat of fishing. The ocean between Galapagos and Cocos Island is a popular place for industrial fishing fleets to work so this monitoring will enable us to highlight the importance of implementing conservation efforts beyond national borders and provide a stronger case for the need to protect migratory species from the threats of industrial fishing.

For scalloped hammerhead sharks, this work has never been so vital following the recent news that their global IUCN Red List status has been revised from Endangered to Critically Endangered, largely due to intense global fishing pressures. The suspected nursery sites in the GMR are small beacons of hope for sustaining the species in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and protecting them has never been more important. Additionally, this monitoring and protection of the species even when they leave the GMR will ensure that these vulnerable sharks are protected throughout their life span.

Find out how to support our Endangered Sharks of Galapagos Programme here.

The work to deliver surveys of shark nursery sites has been made possible thanks to generous support to Galapagos Conservation Trust (GCT) by the Ocean Conservation Trust. The BRUVs workshop was funded by GCT; the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation; Galapagos Science Center; Cesar Peñaherrera and also involved in-kind contributions from the Marine Futures Laboratory at UWA.

Related articles

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

World Oceans Day 2022: Tagging Ocean Giants