Mysterious whale sharks and where to see them in Galapagos

Whale sharks are the largest fish in the sea, yet we still know surprisingly little about these gentle giants.

Hi, I’m Simon, and I have a whale shark problem.

You’d think a giant shark would be easy to find. Whale sharks are the largest of all fish, growing to about 20m in length and 42 tons in weight. Large adults are longer than a school bus and twice as heavy. People are, therefore, often surprised to learn that whale sharks have been rather good at eluding scientists since their discovery in 1828. Apparently even Jacques Cousteau only saw two whale sharks during a lifetime of red wine and ocean exploration.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that scientists became aware that whale sharks can be reliably seen, at least seasonally, at Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia. Over the years since, whale shark feeding areas have been identified at a number of other places, such as Isla Mujeres in Mexico and Mafia island in Tanzania.

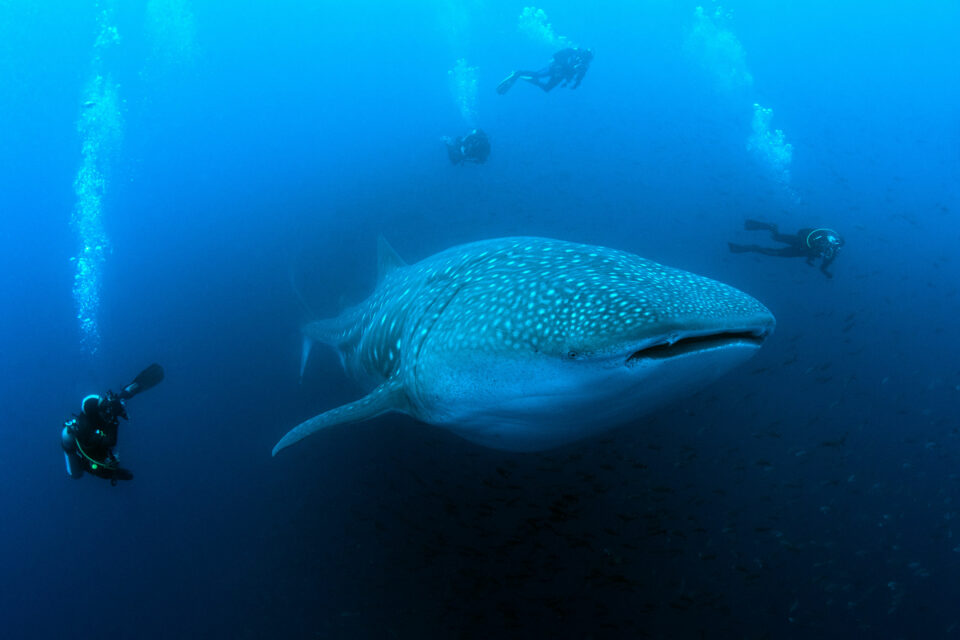

Whale sharks can grow up to 20m in length – that’s longer than a school bus! © Simon Pierce

What’s my problem, then?

All of these sites are dominated by juvenile, or just adult male sharks. That also holds true for other areas where whale sharks are seen, including Madagascar, Mozambique, the Philippines, the Seychelles, and Thailand.

We’re missing the babies. The larger adults. In fact, almost all the female sharks are unaccounted for. It’s a fascinating mystery, but – given that whale sharks are now a globally endangered species – I’m not (just) inspired by curiosity. This conundrum is a huge challenge to effective conservation.

Fortunately, there are a small number of offshore seamounts or volcanic islands that are exceptions to this rule. My other problem? These places are very hard to get to.

I started drafting this article while moored at Darwin, the northernmost island of the Galapagos Islands. Despite my boat being over 300km from the nearest town, this is the best place in the world to see adult female whale sharks. What’s particularly special about Darwin is that most of the sharks that pass by here are huge… and almost all of them appear to be pregnant.

A suspected pregnant whale shark photographed in Galapagos © Simon Pierce

Almost nothing is known about whale shark reproduction. Only one pregnant female has ever been examined by scientists after she was caught in a fishery in Taiwan back in 1995. Incredibly, that singular female was carrying 304 tiny little whale sharks, up to 64 cm long.

We really need to know more and that’s why we’re in Galapagos.

Whale sharks normally spend less than a day at Darwin island. It’s not a place they come to feed. To be honest, we’re not quite sure why they’re here, but the most likely explanation is that they’re calibrating their built-in GPS.

Aerial photograph of Darwin arch and island where large, adult female (and like pregnant) whale sharks are commonly spotted © Simon Pierce

Some sharks can detect the Earth’s magnetic field. Historical volcanic eruptions at Darwin have created concentric rings of magnetically polarised rock on the seafloor, providing a detailed relief map for animals – if they have the right equipment to read it. Their attraction to this area indicates that whale sharks do, and this is backed up by their incredible diving behaviour.

Last year, sadly, none of our satellite tags worked. The crush depth of these tags is around 2km, and the most likely explanation for their failure is that big whale sharks regularly exceed these depths. These extreme dives are probably related to navigation. The Earth’s magnetic intensity varies on a regular daily cycle, peaking around dawn and dusk. That’s when the sharks usually dive deep. We’re assuming that the diving helps the sharks get a more accurate ‘fix’ on their current position.

Cool, huh. That was a slight tangent though, sorry. So, Galapagos. Every whale shark has a unique pattern of spots, meaning that each individual is photo-identifiable. We saw (and satellite-tagged) seven new sharks over 36 dives on our 2017 trip, raising the total number of whale sharks identified from Galapagos to 180. None of these sharks have ever been re-sighted outside of Galapagos.

Whilst the team successfully tagged whale sharks in 2017, the extreme dive depths around Galapagos likely led to their failure to capture data © Simon Pierce

Where are the sharks going? They generally swim right out into the Pacific Ocean, far from any landmass. There’s a long productive zone where cooler waters from the Peruvian coast meet warm tropical waters above the equator and, based on our tracking data, the whale sharks are feeding out there. They’re also, most likely, giving birth in that area too.

What’s next? We’d love to get more people submitting their whale shark photos from Galapagos to the global database at www.whaleshark.org. It’s hard for us to visit Darwin for more than a couple of weeks per year, so photos from visiting divers (from years past, too) are a huge boost to our research.

We still don’t know how often the sharks breed, but it’s likely to only be once every few years. The more photos we have, the faster we can work that out.

Thanks for helping us to solve the mystery.

GCT have been supporting this project for a number of years. You can find out more about the Galapagos Whale Shark Project here. If you would like to support projects like these, then why not become a GCT member today?

You can find out more about Simon and his work on his website: www.simonjpierce.com

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks