Whale shark reproduction

One of the most significant questions that remain unanswered about the ecology of whale sharks is: Where do they give birth?

Finding the answer to this question may be critical in successfully conserving the species because if we are able to protect and monitor “ground zero” we can at least be confident that whale sharks are still reproducing and that there are new generations emerging.

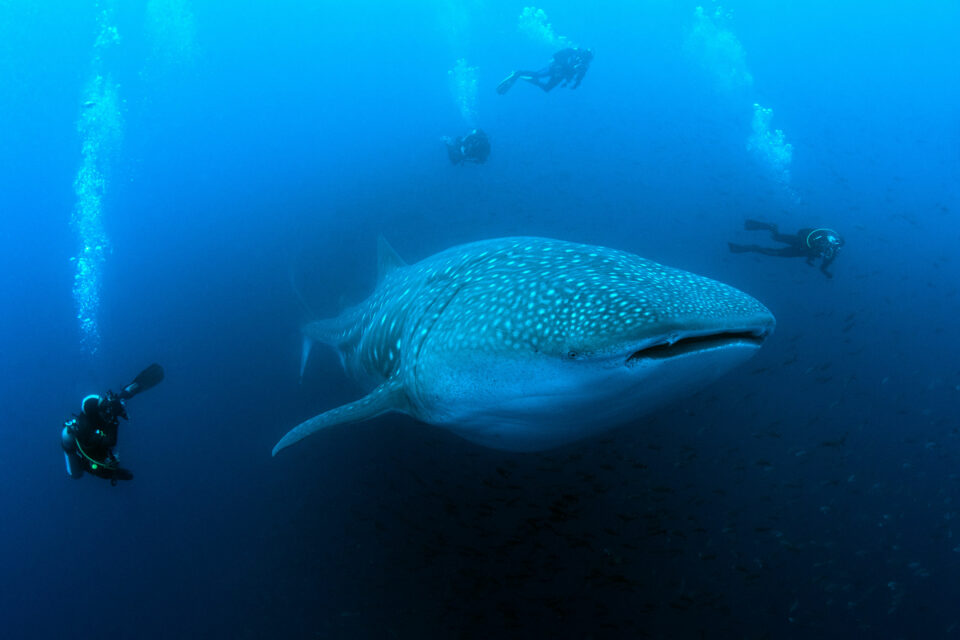

Preliminary findings from the Galapagos Whale Shark Project suggest that as high as 98% of individuals that pass through the marine reserve are female, the vast majority of which are not only mature but appear pregnant. This observation is truly unique among the known whale shark populations worldwide and could indicate that their birthing grounds are relatively close by: a very exciting and important discovery.

But, how do whale sharks reproduce? This is a question that we do know the answer to, but let’s first look at reproduction in sharks as a group. Uniquely, three different modes of reproduction have evolved in the sharks and rays (the elasmobranchs), namely oviparity, viviparity and ovoviviparity.

Oviparous species, like many other fish, lay eggs. Eggs are typically brown in colour and have a leathery case protecting the embryo. If you have ever taken a stroll along the beach and found a “mermaid’s purse”, this is the empty egg shell from an elasmobranch (*see footnote). Whilst inside the egg case the embryo gets all the nutrients that it requires from the yolk of the egg. Oviparous species include the Port Jackson shark and the lesser spotted dogfish.

Viviparous species give birth to live young. This form is similar to reproduction in mammals in that there is a placental link between the developing embryo and the mother through which nutrients are transferred (similar to an umbilicus in humans). Species that have evolved to use this method include the hammerhead and blue sharks.

Finally, there are ovoviviparous species which also give birth to live young but have a different method of internal nourishment. An embryo’s initial development occurs within an egg, gaining nutrients from the yolk, but the embryo emerges from the egg whilst still inside the mother. Once out of the egg, it is nourished by secretions from special glands within the mother until it is ready to be born. This method is the most common among elasmobranchs and is used in species such as sand tiger, great white and basking sharks.

Over 300 whale shark embryos were found in a single female in Taiwan.

Whale sharks are ovoviviparous. This is known from a single pregnant female that was caught in 1995 off the coast of Taiwan. Inside the uterus of this female, which was nicknamed “megamamma supreme”, scientists found over 300 embryos, far exceeding the highest number found in any other shark. Interestingly, many of these embryos were at different stages of development – some were still in their egg cases whilst others had emerged but were still in the uterus. This may signify that females are able to store a male’s sperm, selectively fertilising her eggs over a prolonged period.

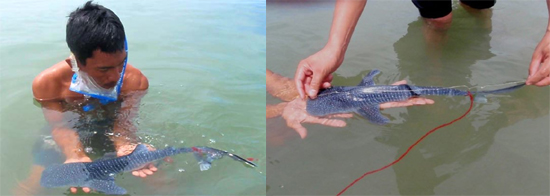

It is thought that whale sharks are born between 40 – 60cm but strangely there are very few recorded sightings of individuals below 3m and it is not known where they spend their time before reaching this size. One notable exception to this is a whale shark that was found by fishermen in the Philippines in 2009. The shark measured just 38cm. To see a video of this encounter, click here.

A 38cm whale shark found in the Philippines. (c)WWF

The fact that so little is known about where whale sharks are born and spend the first few years of life highlights the importance of the research being conducted in Galapagos. If their pupping grounds can be located, protected and monitored, the long-term conservation of this species will be much more secure.

*If you find a mermaids purse on the beach and want to be a part of UK shark research, visit the Shark Trust’s Great Eggcase Hunt webpage.

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks