Searching for Shark Nurseries

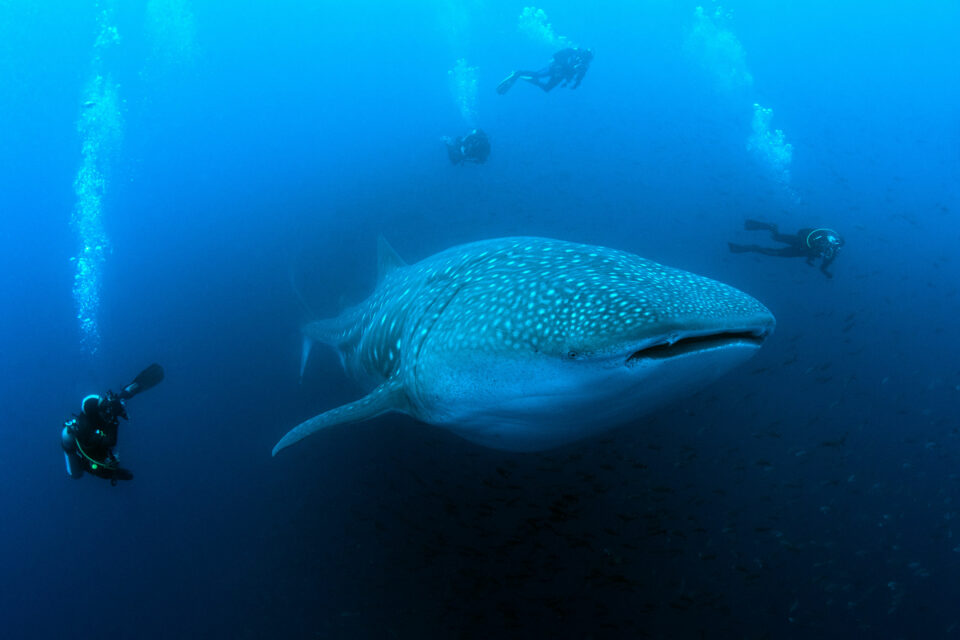

The Galapagos Marine Reserve has one of the highest abundances of sharks in the world, but we are still learning about the early stages of their lives, which is important in order to ensure that they are fully protected.

Supported by Galapagos Conservation Trust, Lauren Goodman is carrying out vital research into shark nursery grounds in the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) over the next three years, using state-of-the-art drone technology. Lauren is a Graduate Researcher from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, based at the Galapagos Science Center (GSC) on San Cristobal island alongside co-supervisor, and GCT science partner, Dr Alex Hearn.

Galapagos is well-known for its diverse marine life and the Islands are famous for the high density of sharks located within the GMR . One of the more commonly encountered sharks around the Islands is the blacktip reef shark. This particular species is known to give birth to babies in nearshore habitats around the GMR and the babies then use these areas during their first year of life. The potential nursery areas are particularly important because they likely contribute more sharks to the adult shark population than other habitats.

“Picture this. You are out in the field with a birds-eye view of a completely clear lagoon, waters the colour of turquoise and white sandy bottoms. Then, all of a sudden, you see it: sharks and not just any sharks. They are babies.”

Lauren admits that spotting her first juvenile blacktip shark didn’t necessarily go as smoothly as that – in reality, it took three days to notice the first baby shark in the drone footage.

To understand and protect shark populations in Galapagos firstly, we need to study their densities and the methodology Lauren and her team use is simple. First, at each site, Lauren will fly a predefined path filming videos with the drone. These flights include areas that are currently believed to potentially be shark nursery habitats and areas where you would not expect to find any sharks.

When the drone flight is complete, a large gillnet (a fishing net with buoys on top that move when something is caught) is thrown into the water and the area of interest is blocked off for an hour. During this time if sharks are caught in the net, they are safely captured, tagged, and health measurements are taken. The number of sharks caught in the net within one hour is then compared to the number captured on video by the drone. A ranked system measuring shark abundance across sites using both survey methods will allow the researchers to determine which sites have the highest abundance of baby sharks and how each method compares within and across sites.

While simple, this research is incredibly important to better understand where these juvenile sharks are and what is the best way to measure their abundance. Lauren and her team think that drone surveys may prove more efficient and less invasive than the traditional methods used to understand the abundance of baby sharks. Through her research, Lauren hopes to influence the expansion and protection of essential nurseries and marine habitats around the Archipelago.

This pilot study is largely focused on the island of San Cristobal but there is potential for expansion across the Islands. This technology could also extend to researching nurseries of multiple species of shark, like the endangered scalloped hammerhead shark, and improve the population surveys of all sharks in Galapagos.

This blog has been adapted from an in our Spring/Summer 2019 edition of Galapagos Matters, which is now available online here.

Special thanks to the National Marine Aquarium, who are key supporters of our Endangered Sharks of Galapagos programme.

Become a GCT member or donate today to help us protect sharks in Galapagos and continue this important work.

Related articles

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

World Oceans Day 2022: Tagging Ocean Giants