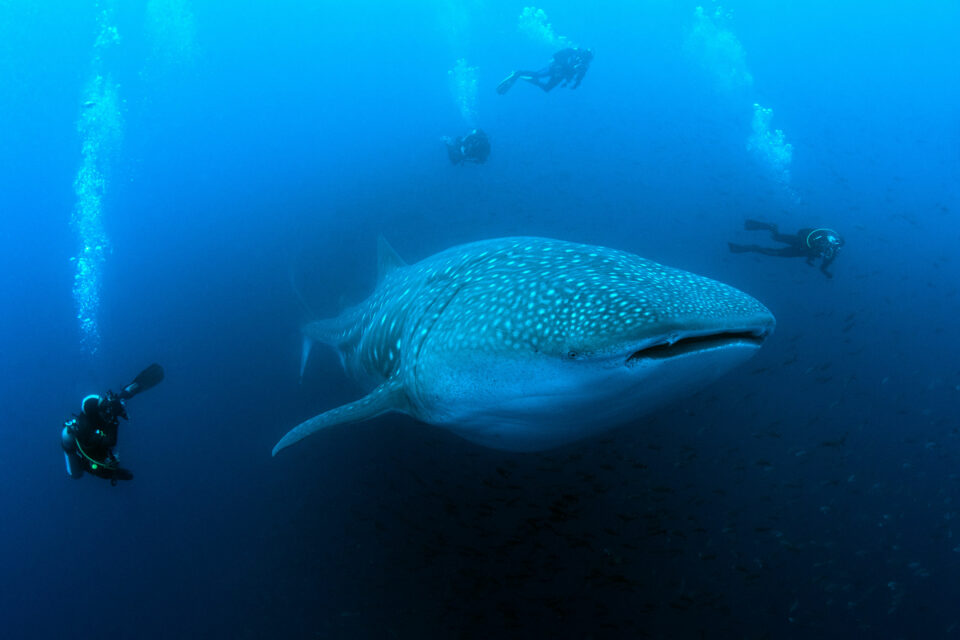

Galapagos Whale Shark Project Update

Despite the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Galapagos Whale Shark Project team were able to undertake a two-week field trip in August 2020 to Darwin and Wolf in the north of the Archipelago to further their important research.

Whale sharks, like many shark species, are under threat. They are listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Even though they are protected from international trade by CITES, their populations are declining as they are subject to incidental bycatch by fishing vessels and are targeted by others for their fins and oil. They are also susceptible to ocean plastic pollution and vessel strikes. However, relatively little is known about their movements and biology, which makes it hard to protect them effectively.

Galapagos Whale Shark Project 2020 results

Despite the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Galapagos Whale Shark Project team were able to undertake a two-week field trip in August 2020 to Darwin and Wolf in the north of the Archipelago to further their important research. As reported in our previous blog, the team tagged a total of 10 sharks with satellite tags, six of which transmitted successfully and provided new exciting insights into the movements of whale sharks in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

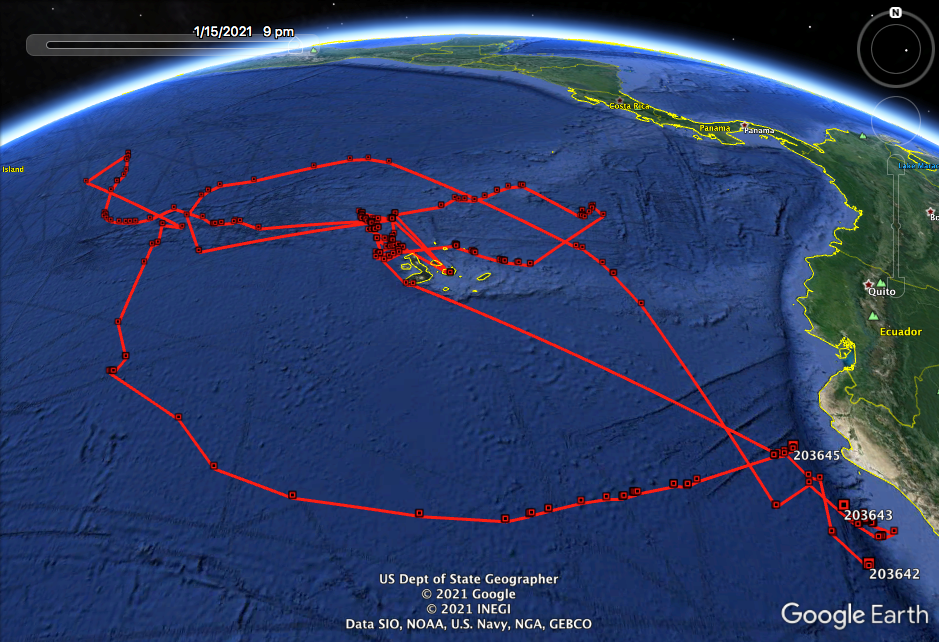

Coco (#203641) was the first tagged whale shark to travel along the Galapagos-Cocos Swimway, a critical marine corridor between the Galapagos Islands and Cocos Island National Park in Costa Rica, which GCT is working to protect. The data from her tag will be used to support the creation of this marine protected area.

Nemo (#203642), named after the Disney character because of her clipped left pectoral fin, was the first whale shark to be recorded leaving and returning to the Galapagos Marine Reserve – a 1,600 km journey that took 80 days. Not only did she come back to Galapagos, she also returned to the site where she had been tagged. This demonstrates the importance of the protected area around Darwin and Wolf – and supports the need to expand the area to ensure the survival of whale sharks and other migratory marine megafauna. In January 2021, she then migrated south to Peru.

Nemo the whale shark has a clipped pectoral fin © GWSP

Johanita (#203643) followed the most common route of tagged whale sharks, north towards the Galapagos Rift Zone. She then turned west, looping back along the Cocos-Galapagos Swimway, where she spent a considerable time, and then headed south towards the Ecuador/Peru border. She disappeared after January 16, just off the Chile/Peru trench but this is not uncommon as female whale sharks dive and remain undetected for weeks at a time in the area off the continental shelf of Northern Peru.

The only juvenile and male tagged in 2020 (#203645) has also provided exciting tracks, suggesting that juveniles move differently from adults. He reached the most northerly point of any individuals tagged so far and then headed south. In January he was found in a similar area to Nemo and Johanita.

The juvenile male whale shark being tagged in 2020 © GWSP

Tracks from Johanita, Nemo and the juvenile male in January 2021 © GWSP

La Niña

The data from 2020 also provided some insight into how the climate might affect whale sharks. Around 50% of the tagged sharks ranged further north than in previous years, which is thought to be related to the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) associated with a La Niña event. This occurs every few years when the SSTs are lower than average throughout the Eastern Tropical Pacific. La Niña events are considered the opposite of El Niño events when the area is subjected to higher surface water temperatures.

Increased illegal fishing activity

Sadly, the team found evidence of illegal fishing during their field trip. They found three shark species, Galapagos, silky and hammerhead, with hooks in the mouth or the eye, resulting from long-line fishing. In addition, they found fish aggregation devices (FADs), composed of a net with a bamboo raft, bait and a radio buoy. These are set to drift through the GMR, attracting fish and sharks which are then caught by long-lines set outside of the Reserve. If FADs get caught up on the seafloor, they can end up entangling and drowning marine life such as sharks and turtles.

Industrial and illegal fishing are increasing in the Eastern Tropical Pacific as fish stocks decrease elsewhere in the world. Research from the Galapagos Whale Shark Project, which we support, is vital in helping us to ensure that sharks and other marine fauna get the protection that they deserve.

Ways to get involved

Worryingly, especially after Hope’s disappearance, all three whale sharks have been in areas of high fishing pressure whilst migrating. These findings show the importance of shielding Galapagos’ precious marine life from the threats of industrial fishing. We don’t want to see animals like Coco, Nemo and Johanita meet the same fate as Hope. Please help us protect endangered whale sharks and other threatened marine species by donating to GCT today.

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks