What do tortoises, seabirds and whale sharks have in common?

The answer is that GCT funds projects that are working to conserve them! Here are the latest updates from the field.

Galapagos Whale Shark Project

The Galapagos Whale Shark Project has been tagging and photo-IDing whale sharks at Darwin Island in Galapagos since 2011. This research is undertaken in hope that the data will lead to increased legislation for the biggest fish in the sea- this year whale sharks were listed on the IUCN Red List as endangered, creating a stronger urgency to find out more about their life histories to ensure proper protection strategies are in place.

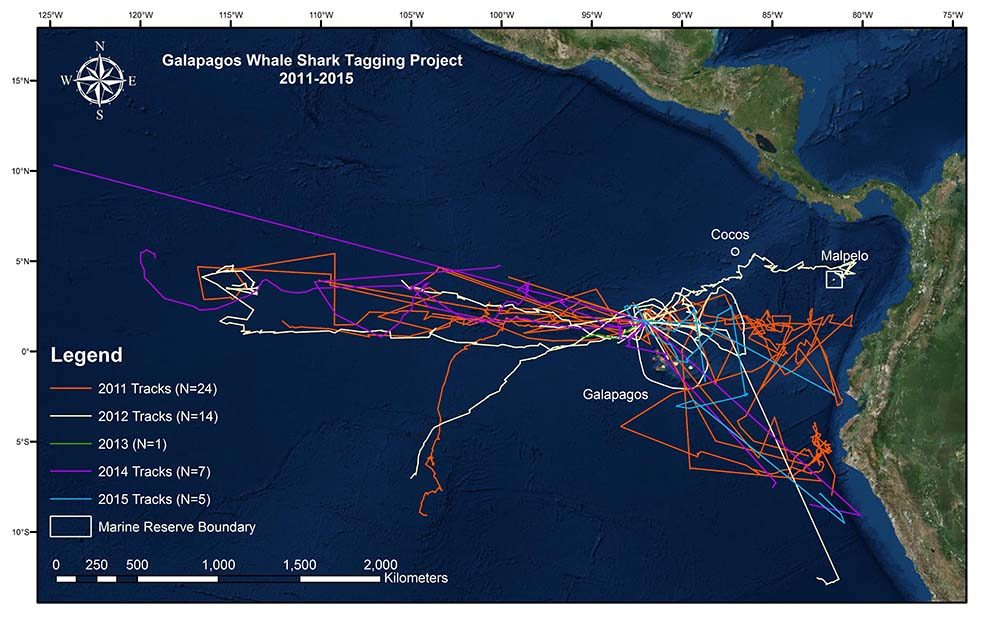

Most previous whale shark tracking projects have focussed on immature individuals along mainland coastlines, but the Galapagos project focusses on a large aggregation of adult female whale sharks in an offshore, mid-ocean location. Amongst other things, the tracking data has allowed the team to show that whale sharks return to Darwin Island after moving large distances into the open ocean as well as an association with the coastlines of mainland Ecuador and Peru. The tags have provided the project with a wealth of new information and the hard work of the researchers has paid off with a scientific paper about the early years just published in the peer-reviewed journal Marine Biology. You can read the abstract here.

The team are currently out at Darwin again trialling new tags and trying to establish whether any of the females are pregnant so watch this space for more updates.

Whale Shark Tracks 2011-2015 © GWSP

Seabird Surveys

Another project that GCT funds led by the Charles Darwin Foundation in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park, monitors three of the seabird species along the coast of Galapagos; the waved albatross, flightless cormorant and the Galapagos penguin. The sea birds are regularly surveyed in order to monitor population numbers. During the summer, the team visited Espanola, Isabela and Fernandina islands to continue this vital research.

All three species are under threat. The waved albatross, the largest bird in Galapagos with a wingspan of up to 2.5m, has been listed as critically endangered since 2007 due to its restricted breeding range. It only breeds on one island in Galapagos, Espanola, with an additional tiny population of about 20 pairs found off the coast of Ecuador.

The flightless cormorant is a fantastic example of evolution. The birds have lost the ability to fly but are wonderfully adapted to hunting in their surrounding marine environment. Until recently, flightless cormorants were also listed as endangered but have been re-categorised as vulnerable – a great sign that the populations may be showing signs of recovery.

Galapagos penguins are the world’s rarest penguins. Found exclusively in the Galapagos Islands, their total population is less than 1,000 breeding pairs, and are classed as endangered.

Data collected includes key population demographics which are used to estimate rates of penguin survival and reproduction, and meteorological conditions to assess how the changing environment is affecting populations. Veterinary samples are also taken to assess health and to test for the presence of diseases such as avian malaria. Additionally, researchers record the presence of introduced mammal species such as rats and cats, providing a valuable indication as to whether invasive species management strategies are working or if more needs to be done.

During the 2016 summer season, 92 penguins, 43 cormorants and 210 albatross were assessed. Sadly it appears that this year’s El Niño event had a negative effect on all three species’ reproductive success with less nests encountered than in previous year. It was found, however, that evidence of invasive predators has continued to decline, thanks to eradication efforts with seabird nests found in areas where they struggled in previous years. A sign of conservation success!

©Intl Keither FCD 2016

Tortoise Tracking

The Galapagos Tortoise Ecology Movement Programme is made up of a team of experts who monitor the movements of the iconic Galapagos giant tortoise. Despite being internationally renowned, until recently very little was actually known about the population and migration of the tortoises, making it harder to conserve them. In addition to tracking and monitoring the adult tortoises, the programme has been looking at the ‘Lost Years’ of the tortoises by monitoring nests and tracking hatchlings. Since 2013, 95 nests have been monitored and a small sample of hatchlings have been tracked using radio transmitters – the first time such techniques have been used on giant tortoises. The data that comes out of this project will be vital to understanding the life history of the tortoise but has so far shown that nest location is extremely important in determining reproductive success.

Favoured tortoise habitat on Santa Cruz is in the lush highlands where food for the giant tortoises is plentiful. This nutrient-rich soil is also great for farmers to grow crops to sell as well as their own food. Due to this potential conflict, the Galapagos Tortoise Ecology Movement Programme has enlisted the help of local farmers to help monitor the tortoise’s movements and habits.

Moz the hatchling ©GTMEP

Help us help them…

If you would like to help fund any of these projects , please visit our donations page. In addition, you could visit our adoptions page to adopt your favourite endangered Galapagos animal. All proceeds from adoptions go towards the ongoing protection and conservation of the fascinating Galapagos wildlife. Thank you.