Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos Programme: Oceanography Project Update

An update on the oceanography work led by Dr Erik van Sebille from Utrecht University as part of our Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos Programme.

Galapagos Conservation Trusts’s Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos Programme (PPFG) programme sits within the wider, regional Pacific Plastics: Science to Solutions network. There are three streams of this work:

- Sources: establishing the sources and environmental pathways of plastic waste in Galapagos through new monitoring tools developed for managers and a targeted reduction of plastic inputs at identified sources.

- Impacts: investigating which Galapagos species and habitats are most at risk from marine plastic and how these threats could be mitigated through species management plans and clean up activities focused on high-risk habitats.

- Solutions: establishing behavioural drivers of plastic usage and irresponsible disposal, breaking down barriers to using alternative products (including supply chain analysis), influencing policy changes and driving effective education and awareness campaigns tailored to schools, fishers and the tourism industry.

Oceanography Overview

The flows of plastic waste into the ocean and the relationship with consumption and waste management systems are poorly understood both in mainland Ecuador and Galapagos. Here we will provide an update on the oceanography work led by Dr Erik van Sebille from Utrecht University which forms part of the Sources stream listed above. This work aims to establish robust scientific approaches to understand and monitor the sources, distribution and fate of plastic waste. This work will culminate in the development of a high-resolution oceanographic model that predicts sources and movements of incoming floating plastic from oceanic sources to enable an efficient clean-up response.

Goal 1: Regional scale model to identify sources of plastics in Galapagos

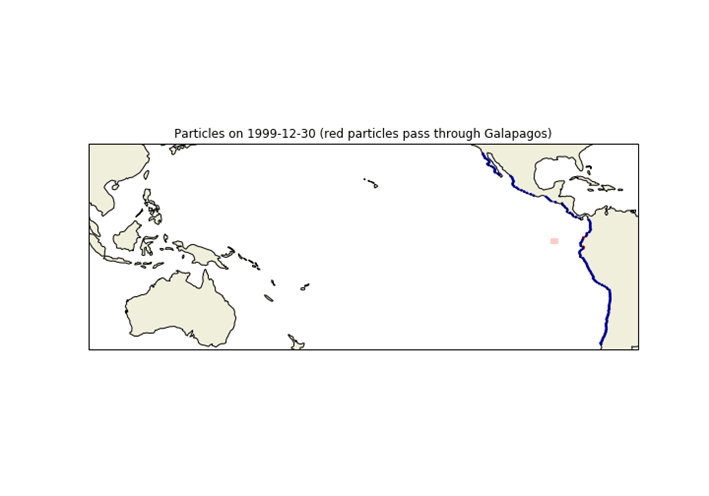

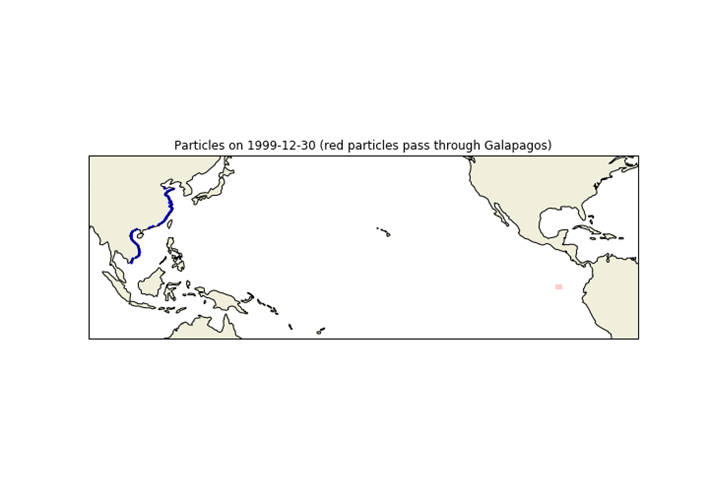

The first step for the team at Utrecht University was to produce a series of predictive oceanographic computer simulations that model the flow of plastics in and around the Galapagos Marine Reserve to answer the first main question: where is plastic coming from and how does it get to Galapagos? Using a continental-scale model, the team concluded that remote sources of plastic pollution to Galapagos are largely from South and Central American coastlines, in particular northern Peru and southern Ecuador (Figure 1). They also concluded that plastic would not pass through the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) if released from Asia (Figure 2). This second finding was particularly important as it implicated the international fishing fleet, especially the Chinese fishing fleet, having poor waste management, as a high volume of Chinese plastic waste is found in Galapagos each year which we now know is unable to come from the mainland.

Goal 2: Creation of a plastic behavioural model specific to Galapagos’ macroplastics including ground truthing the models using drifters

Following the work done at the regional scale, the next step for the team is an archipelago-scale oceanographic model. This model has been finished but one final improvement is needed. Since September 2021, Inti Keith, Principal Investigator of Marine Invasive Species at Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) and her team have released almost 50 drifters (floating sensors) around the Archipelago.

From left to right, top to bottom: a) drifter, b) Inti Keith with a drifter about to be deployed, c) CDF and GNP scientists and d) drifter deployed at sea. © Rashid Cruz, CDF

These drifters are carried by ocean currents as plastic would be and relay real-time data on their location to the team at Utrecht. Excitingly, the drifters can be seen in real-time on Utrecht University’s website. We will use this data to further refine the model, identifying sources closer to the GMR (e.g. fisheries) and predict how pollution moves within the GMR to inform cleanups, as well as education and advocacy campaigns, increasing the cost-effectiveness and impact of each.

Goal 3: Development of a plastic forecast tool for Galapagos

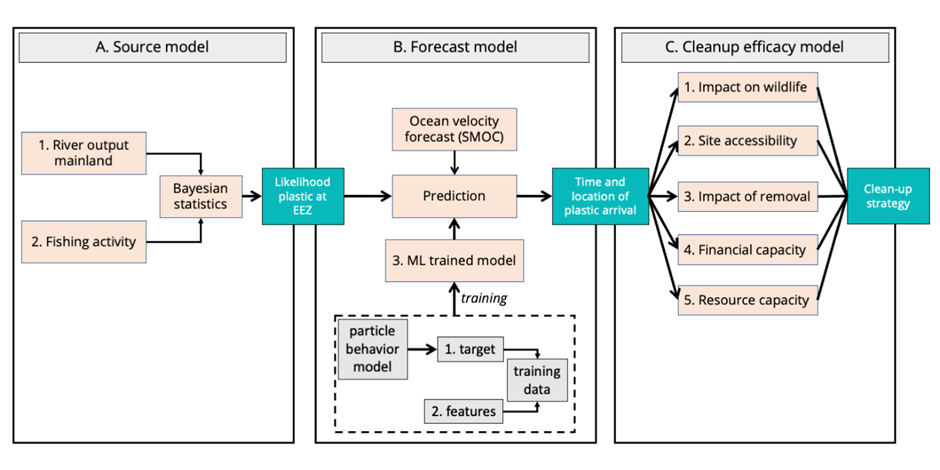

The final stage of this work will be to develop a forecasting tool to support efficient clean-ups. To do this, we will produce three complementary models. Firstly, a Master’s student will model the distribution of plastics in the open ocean and around the GMR based on the sources of plastics (fishing activity and river outputs from the mainland). Secondly, this will feed into a forecast model predicting where and when plastic will arrive in Galapagos. Thirdly, the cleanup efficiency model will be optimised for the most cost-effective, least invasive, and most impactful cleanup locations. Finally, this model will be developed into a real-time app, informing Galapagos National Park (GNP) teams on where clean up resources should be focused.

What can you do to help?

Please help us tackle plastic pollution today by giving a donation or joining up as a GCT member.

Related articles

New research shows that Galapagos giant tortoises are ingesting plastic waste

Creating a circular economy for plastics in Galapagos