How to control a parasite

The invasive parasitic fly Philornis downsi is a serious threat to the survival of at least six species of Galapagos land bird, including the Critically Endangered mangrove finch.

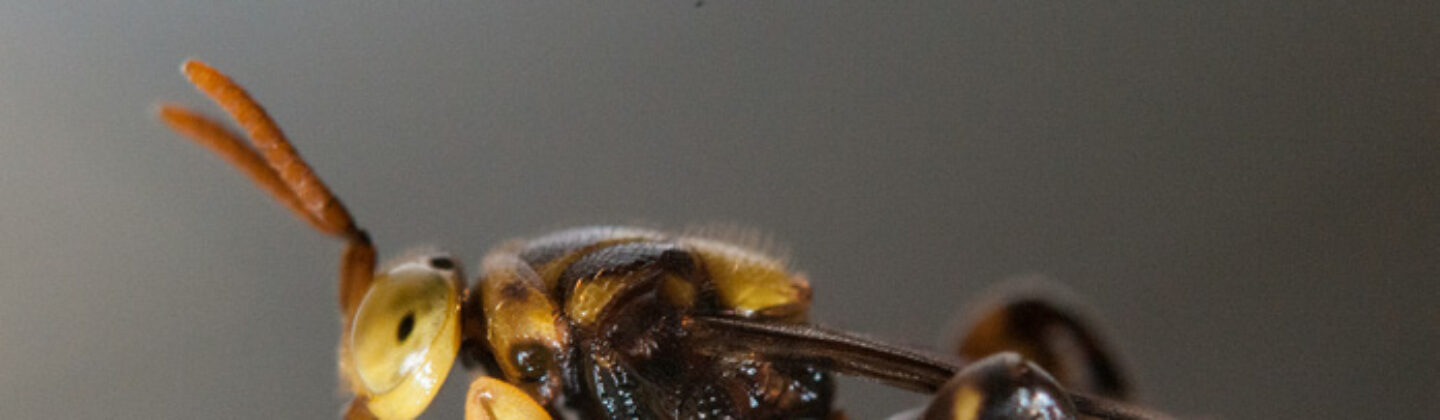

As we made preparations for fieldwork in 2020, the weather was our biggest concern. Little did we know that there would be a global pandemic that would shut down research for three-and-a-half months in the middle of the bird-breeding season, a crucial window for testing methods to control the invasive parasitic fly Philornis downsi, enemy number one of the smaller Galapagos landbirds. These invasive flies, introduced from mainland Ecuador by accident, are experts at locating bird nests, where they lay their own eggs. Once the maggots hatch, they feed off the blood of young chicks, sometimes killing an entire brood. To date, P. downsi is known to attack 21 different landbirds, more than half of which are species of Galapagos finch, and is a serious threat to the survival of at least six species including the Critically Endangered mangrove finch. The parasitic fly also threatens some populations of the little vermilion flycatcher, the most colourful landbird in Galapagos.

In a race against time, the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) and the Galapagos National Park (GNP) are coordinating a multi-institutional and multi-country project to research the biology and ecology of this little-known fly, with a view to developing effective, environmentally friendly means of control. One promising approach is biological control, which involves introducing one of the fly’s natural enemies from its native range to the Archipelago. Exploratory surveys on mainland Ecuador, led by the University of Minnesota and CDF, have identified a small wasp, Conura annulifera, that is itself a parasite of P. downsi. After five years of careful work, results indicate that this wasp is a Philornis specialist. We now have the go-ahead to bring a small number of wasps into a quarantine facility in Galapagos in order to assess whether it is safe to introduce the wasp to the Islands.

In the meantime, we need to deploy other tools to protect the nests of those species at the greatest risk of extinction. Before COVID-19 brought put an end to our fieldwork this year, we were fortunate to have completed some trials injecting a small amount of an insecticide into the base of the nests where the bloodfeeding larvae reside when they are not feeding on the chicks. This work, carried out by CDF, GNP and the University of Vienna, has significantly increased the survival of chicks from four threatened bird species, including the mangrove finch and the little vermilion flycatcher.

In collaboration with scientists from SUNY-ESF and Syracuse University, we are also investigating whether we can use fly pheromones and bird odours to lure adult Philornis flies down from the canopy and into traps. All our efforts to control this deadly parasite require a mix of ingenuity and perseverance. We are fortunate to be working with a large group of dedicated scientists who are not deterred by setbacks like that posed by COVID-19 and who will continue the work to ensure the conservation of the unique landbirds of Galapagos.

This article was originally published in the Autumn-Winter 2020 issue of Galapagos Matters. It has been edited slightly for this blog.

How to help

Why not become a member today for as little as £3 a month, and help to preserve these Islands for years to come? Or head over to our shop to purchase a Galapagos gift such as our animal adoptions.

Related articles

How do we solve the problem of invasive species in Galapagos?

Restoring Floreana: A local perspective