Devil’s Crown – exploring coral habitats in Galapagos

Of all the coral habitats in the Eastern Pacific, Corona del Diablo or the ‘Devil’s Crown’ in Galapagos is certainly one of the most interesting.

Of all the coral habitats in the Eastern Pacific, Corona del Diablo or the ‘Devil’s Crown’ in Galapagos is certainly one of the most interesting.

Despite their location at the equator, the Galapagos Islands do not easily fit the popular perception of a tropical island paradise. In fact, all who have visited can attest to them as rather harsh: rocky, arid, always undecided whether to punish visitors and residents with unusual heat or cold.

We need to understand more about how these corals survive in such a difficult environment in order to protect them © Jonathan Green

For reef corals, most comfortable as denizens of warm, tropical climes, the extreme and fluctuating conditions in the Galapagos waters pose a significant existential challenge. However, difficult environments do not preclude interesting biology.

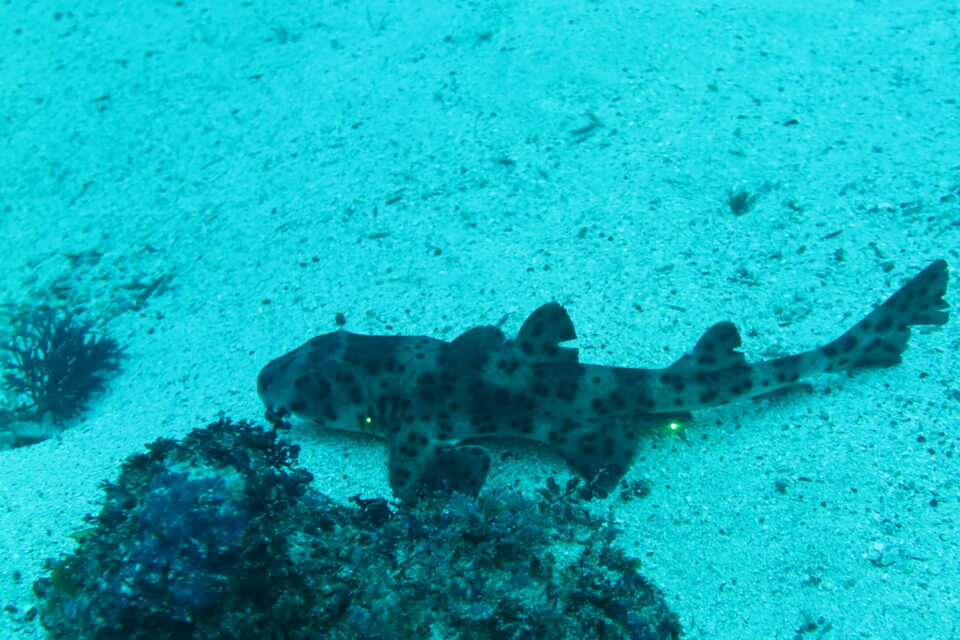

Of all the coral habitats in the Eastern Pacific, Corona del Diablo or the ‘Devil’s Crown’ in Galapagos is certainly one of the most interesting. The island itself, which lies about 1km north of Floreana, is all that remains of an eroded cinder cone, but the atoll-like ring provides the perfect protection for an explosion of coral forms, including many branching Pocillopora and brain-like boulder corals. Even more surprising, however, are dense assemblages of solitary corals on the sandy, barren sea floor just beyond the island’s perimeter, with some of the species not recorded at any other site in Galapagos.

Careful exploration of Devil’s Crown over several decades reveals just how this coral community has changed through time. With these corals having deposited almost 2m of limestone on top of the underlying volcanic basalt and with the use of radiocarbon dating, we estimate that corals have been present in this spot for 7700 years.

This makes the Devil’s Crown corals one of the oldest assemblages in Galapagos. The only coral structures that sit on deeper deposits are found around Darwin and Wolf in the north of the Archipelago, but even they appear to have become established after those at Devil’s Crown.

There is still much to learn about how and why these corals have been doing so well in such a difficult habitat and what the long persistence of this totally isolated outpost population means for the persistence and evolution of these rare and beautiful species.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2021 edition of Galapagos Matters.

How you can help

If you’d like to become a member of Galapagos Conservation Trust from as little as £4 per month, head to our Membership page or make a donation today.

Related articles

A week in the life of a female marine researcher

Galapagos and the Antarctic: A look beneath the surface