From COP27 to COP15: Is a global deal on biodiversity within reach?

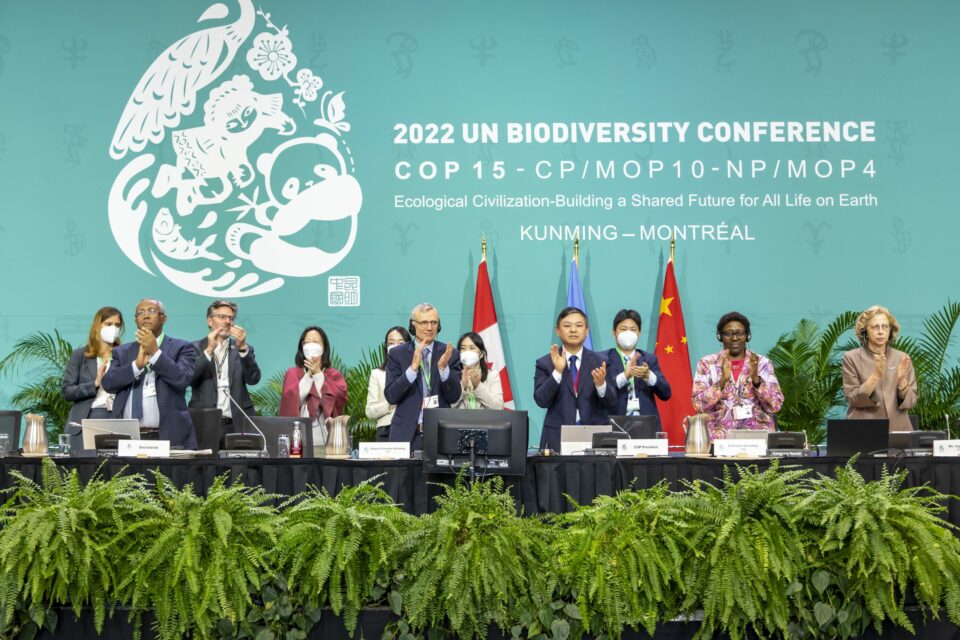

As the dust settles on the disappointing COP27 climate change conference, we are now looking ahead to the COP15 conference on biodiversity in Montreal.

COP27: Successes and failures

After the highs of COP26 last year in Glasgow, including Ecuador’s landmark announcement of the new Hermandad Marine Reserve, COP27 felt for many of those involved like a dispiriting reality check. Overshadowed by the gloomy global economic situation and the war in Ukraine, the conference opened with a blistering address from UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

There was dismay at the number of fossil fuel lobbyists present at the conference, and the prospects of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels seem increasingly remote. Nevertheless, there were some positives to come out of COP27.

For the first time, an agreement was reached on providing poorer countries with financial assistance to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change, known as ‘loss and damage’. The final agreement highlighted for the first time the importance of safeguarding food security and water systems, although without yet backing this up with concrete actions. There is also growing recognition of the way in which the climate and biodiversity crises intersect, underlining why it is so vital that we build climate resilience in Galapagos by restoring island ecosystems and protecting oceans.

We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.

COP15 and the Global Biodiversity Framework

The key aim at COP15 is to secure a global agreement on halting and reversing biodiversity loss, comparable in its scope and ambition to the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. The draft treaty, known as the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), maps out a route to achieving a world that is ‘nature-positive’ by 2030, and includes 22 targets to guide policymakers, such as protecting at least 30% of land and sea areas globally, controlling or eradicating invasive alien species, and eliminating the discharge of plastic waste.

If a deal can be agreed in Montreal, then the next steps will be financing and implementing the solutions required to meet the GBF targets. Organisations such as Galapagos Conservation Trust and our partners will be at the forefront of delivering these solutions, and our strategy is closely aligned with the GBF. We are making the case for greater marine protection through our work demonstrating the impact of unsustainable fishing, and we are working to tackle threats to marine life such as plastic pollution and fish aggregating devices (FADs). Through programmes such as the restoration of Floreana island we are working to control invasive alien species and reintroduce locally extinct species, which will boost biodiversity and repair degraded habitats. And underpinning all of this is our commitment to build capacity on the Islands and engage local communities in conservation, creating the green jobs of the future.

Commitment to an ‘Ecological Civilisation’

Along with the outcome of the treaty negotiations, the other thing that we will be watching closely at COP15 is the role of and commitment from China. The Kunming Declaration on Biodiversity Conservation, led by China and adopted in October 2021 by over 100 countries following the first (virtual) session of the COP15 talks, sets out a number of commitments, including the development and implementation of a global biodiversity framework.

The Kunming Declaration is notable for its reference to ‘ecological civilisation’, an approach to conservation that links environmental protection to economic development. President Xi Jinping also used the opening session of last year’s talks to announce the ¥1.5 billion ($230 million) Kunming Biodiversity Fund for the protection of flora and fauna in the developing world.

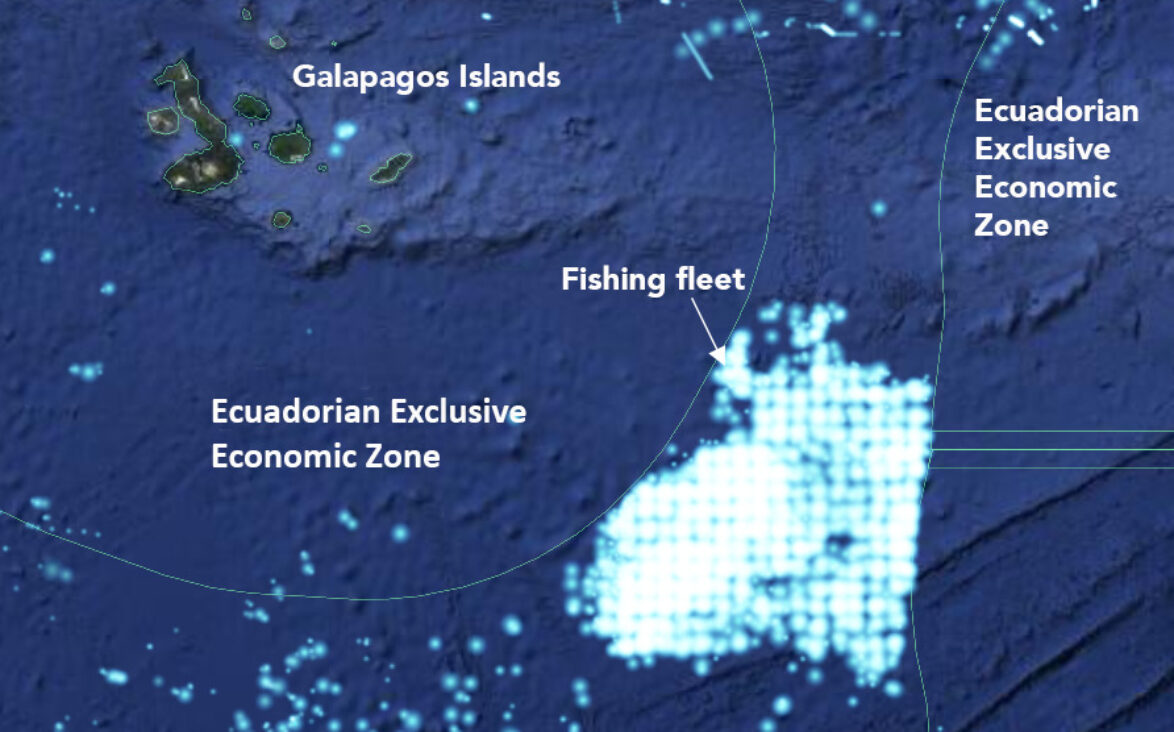

Balanced against all of this are the activities that are causing the same problems that the GBF aims to address. One of the biggest threats to marine species in Galapagos is unsustainable fishing, with huge distant water fishing fleets registered in China operating on the periphery of the Galapagos Marine Reserve. The waters surrounding the Islands are home to one of the highest concentration of sharks in the world, many of which are being caught as bycatch. Although catching sharks deliberately is illegal, if caught as bycatch and landed, it is then legal to keep and sell them, with their fins ending up in soup. In 2017, the Galapagos National Park intercepted a Chinese fishing boat which contained over 6,000 individual sharks. In addition, research funded by GCT has shown that much of the plastic that washes up in Galapagos originates from industrial fishing fleets dumping plastic waste at sea.

It is increasingly clear that solving the issues that threaten the wildlife of Galapagos, such as overfishing, plastic pollution, climate change and the illegal wildlife trade, will require strong leadership, with all nations committing to implement the solutions required to meet the GBF targets.

30 %

by 2030 - the global goal for protecting land and sea

Related articles

COP15: A historic agreement on halting biodiversity loss

Galapagos Day 2022: Protecting Species & Preventing Extinctions