Charting change in the Galapagos Marine Reserve

As we celebrate 25 years of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, GCT's Dr Jen Jones reflects on her experiences as part of a multi-disciplinary expedition led by the legendary Dr Sylvia Earle.

Approaching the Argo, the Costa Rican research vessel that would be home for the next 11 days, I looked at our team and pinched myself. Before it had begun, I knew this trip would be special; an inspirational group of people committed to protecting the ocean, representing all kinds of different research and communications disciplines, from at least eight different organisations across the world. Uniting us all was the true belief that this multi-disciplinary approach is essential for understanding what is really happening to our oceans, and, crucially, that this will help us to design solutions.

It’s 25 years since the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) was established in 1998, protecting the 40 nautical miles from the Islands’ coastlines. A vital lifeline for many ocean species, the GMR was extended in 2022 to protect an additional 60,000 km2 along the Cocos-Galapagos Swimway, an important migratory path for many sharks, turtles and whales. This means that the total area of ocean protected is now 198,000 km2, but changes both inside and outside the marine reserve in this last quarter of a century have been happening at an extremely rapid rate. Between 1998 and 2022, tourism in Galapagos has grown from 65,000 to 268,000 visitors per year and the local population is estimated to have nearly doubled to over 30,000.

Ocean Protection Appeal

Our vision of the seas around Galapagos free of pollution and full of life, but we need your help. Support our Appeal and help us fight back for the marine life of Galapagos.

Outside the boundary of the marine reserve, the global appetite for seafood has boomed, with some 200 million tonnes harvested through wild catch and aquaculture every year, as has the use of plastics. Plastic production has doubled in this timeframe, with waste leakage and pollution unfortunately tracking the same trend, having major impacts on ocean ecosystems.

The message of our expedition is clear: the health of the ocean determines the health of the land, and is therefore also crucial for we humans, no matter how far from the coast we live. We need to give ocean protection the same precedence we do to land because, as ‘Her Royal Deepness’ Dr Sylvia Earle of Mission Blue, our expedition leader, famously says: “No blue, no green.”

Ocean biodiversity baselines

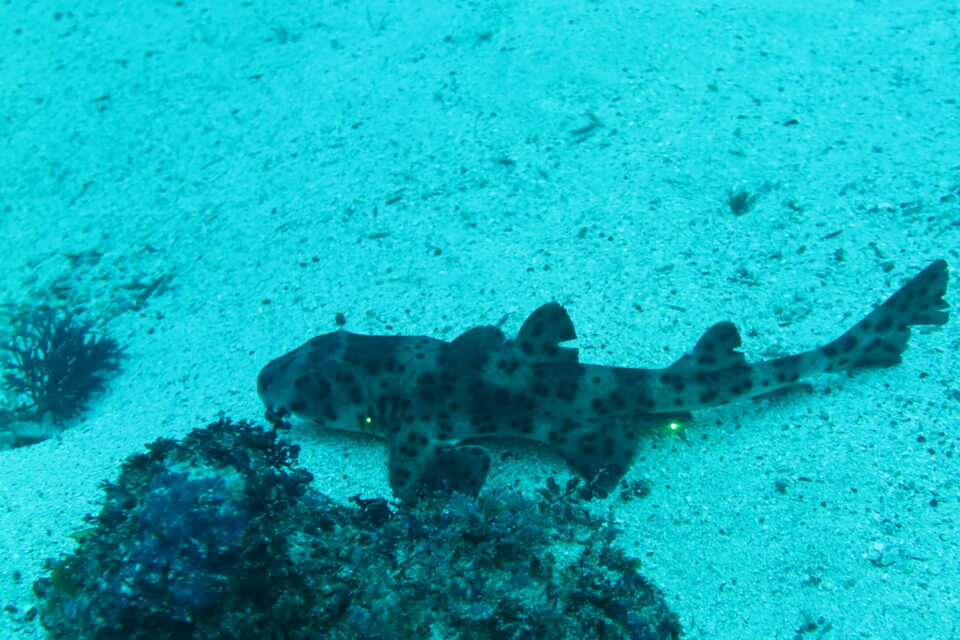

One way of understanding the health of the ocean is to map species distributions and count populations of important species. Ideally this would include species representing different parts of the ecosystem, as we had on this expedition.

Seeking ocean plants were Salomé Buglass of the University of British Columbia and Charles Darwin Foundation, and the aforementioned Dr Sylvia Earle, aiming to map deep sea kelp forests that are extremely rare in the tropics. Deep sea invertebrates such as corals and sponges were documented by Salomé and Jenifer Suarez, a Galapagos National Park Ranger and marine biologist with phenomenal coral identification skills.

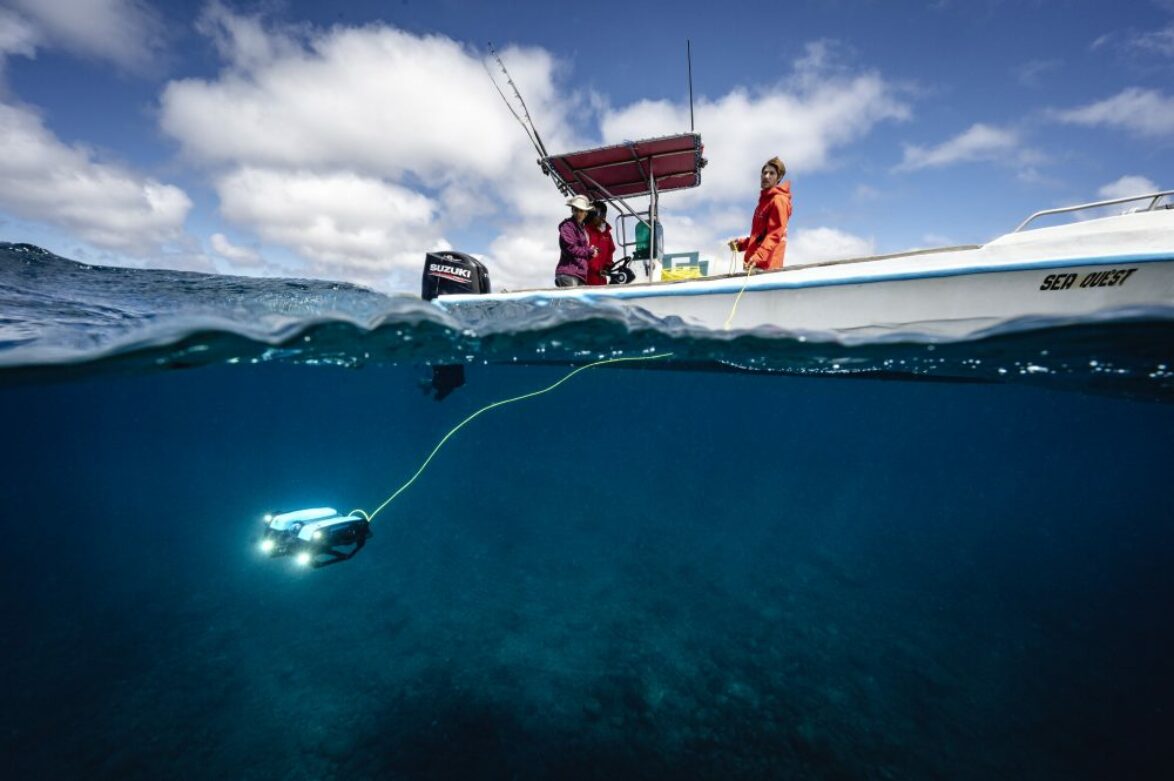

Seeking ‘forgotten species’ of the marine reserve that have been under-represented in studies to date, such as slipper lobsters and seahorses, was our science lead Dr Alex Hearn from the Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ) and MigraMar. Running a series of baited remote underwater video (BRUV) surveys to count sharks, rays, turtles and the odd visiting dolphin were Daniel Armijos and Manolo Yepez, supplemented by hydrophone recordings by Taylor Griffith to listen to goings-on along reefs and in the open water, including listening out for whales.

On the coast, Dr Susana Cardenas from USFQ and Alberto Proaño, Galapagos National Park Ranger, surveyed seabirds. Filling in all the gaps in between was environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling led by Dr Diana Pazmiño. Using this technique, it is possible to detect, from a drop of water, hundreds of organisms that have left minute traces.

Marine plastic pollution

My contribution to the expedition was to measure one of the most significant changes we have seen in the last 25 years: marine plastic pollution. Very little data currently exist about plastic pollution in the west and north of the marine reserve where the majority of endangered marine life is found. Plastic pollution on beaches in the west of the Archipelago was at low quantities, as we would predict, but as always, it was still present. In addition to surveying for plastics along the coast, I also sampled microplastics in seawater that are currently being analysed with the University of Exeter.

The message of our expedition is clear: the health of the ocean determines the health of the land, and is therefore also crucial for we humans, no matter how far from the coast we live.

Diving down to the depths

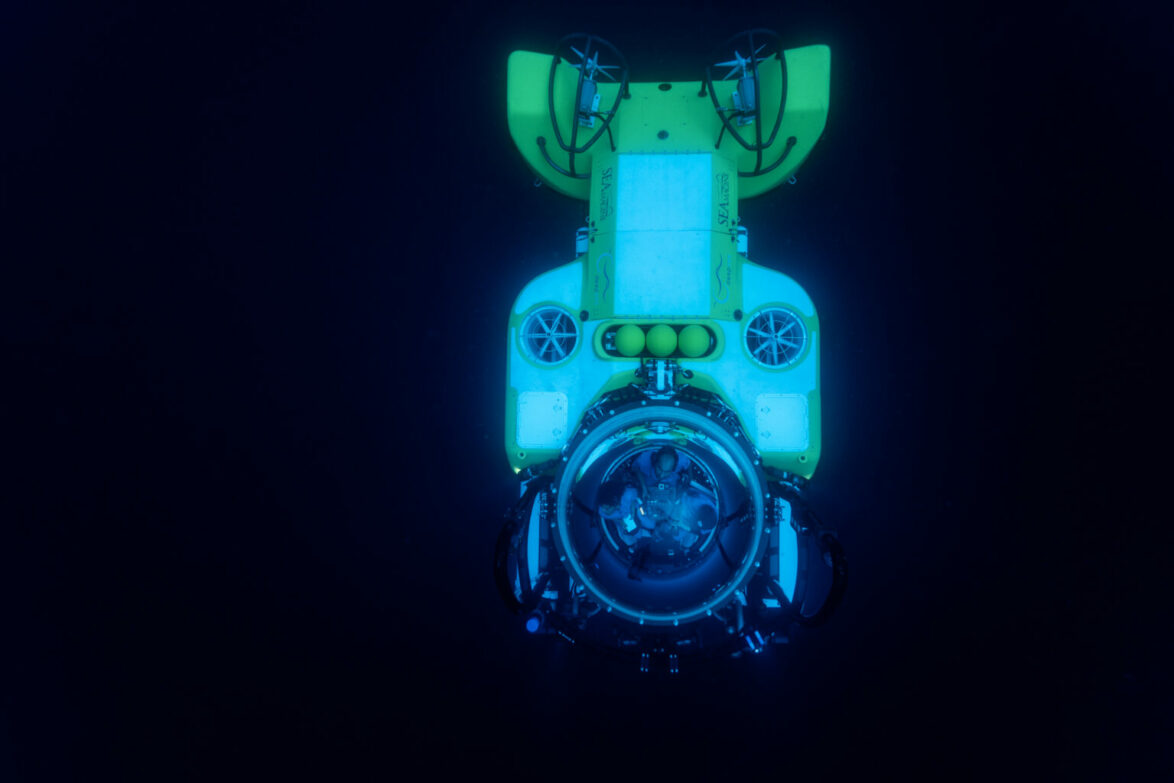

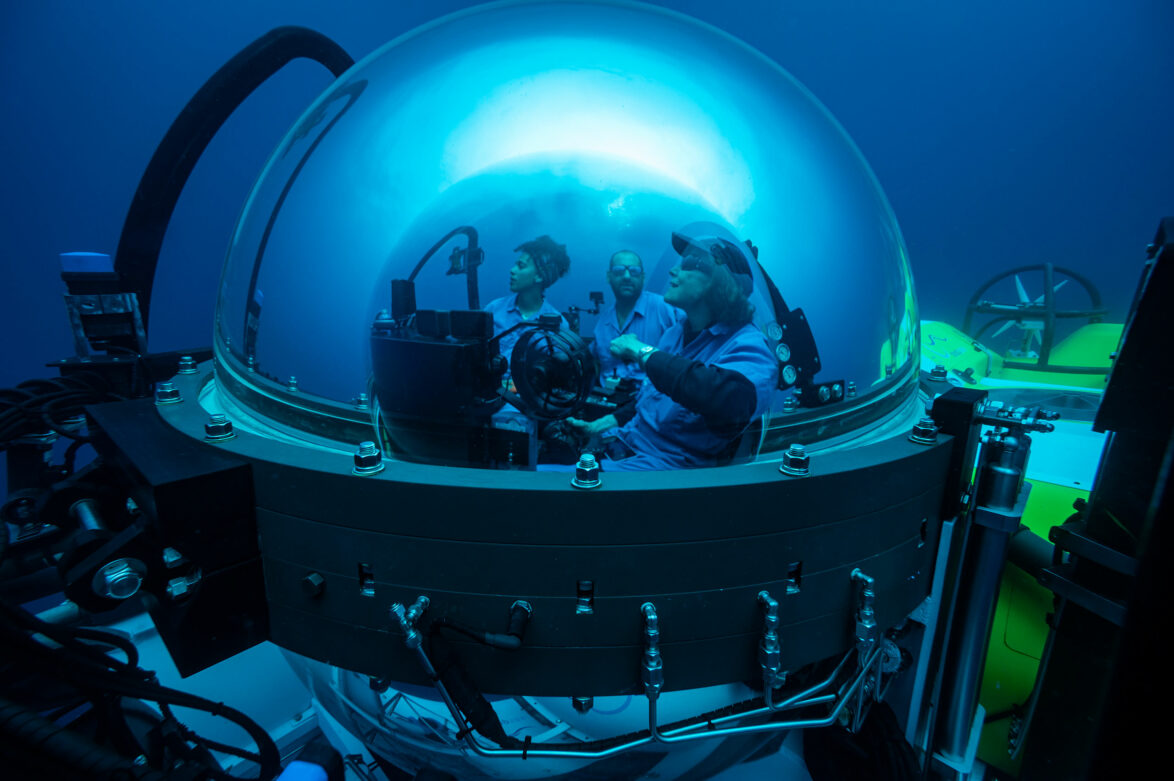

Never in my wildest dreams did most of us on board expect to experience a submarine dive. It has always been one of my biggest dreams, ever since watching the Deep Sea episode on the BBC’s original Blue Planet in 2001 as a teenager, narrated, of course, by Sir David Attenborough. Nothing could possibly prepare you for the sensation of being in a submarine, as that wonderful blue gradient gets darker and you await glimpses of lifeforms that, unlike humans, are adapted to life at high pressure and low temperatures. My dive was down to 200 metres depth off the coast of Marchena island, surveying a piece of sea floor never seen before by human eyes. We saw the whole library of marine species groups: corals, sponges, juvenile fish of many species, shrimp, schools of large fish and a ray. The fragility of the ecosystem was really moving. A slow-paced environment that is so far from most human minds, but there is starting to be evidence of our impact even here.

Each evening after dinner, we gathered as a group to watch the hours of footage from the day’s submarine dives, and to compare notes on sightings at the surface. Every night we were completely rapt – this was better than any series you could get on a streaming service. “Like going to space, but better!” – everyone agreed.

Nothing could possibly prepare you for the sensation of being in a submarine, as that wonderful blue gradient gets darker and you await glimpses of lifeforms that, unlike humans, are adapted to life at high pressure and low temperatures.

Bearing witness

Sylvia has been under Galapagos’ spell since the 1960s when her research on deep sea kelp first took her to the Islands. Also in our team was legendary Galapagos photographer, Tui de Roy, who has known Sylvia since her first visits. Both consider themselves witnesses of human impacts in Galapagos over this time. Both of these women are also remarkable role models for the researchers present, and we learnt so much from their experiences.

Although much of what they have witnessed has been shocking in terms of the consequences for wildlife, we could also see that we were bearing witness to a new phase, where we have much higher female representation in science and multi-disciplinary collaborations are springing up to provide the driving force needed to solve these huge global problems.

We were sharing stories about what had changed in that time, and how many more female scientists there are now, running the show in many cases, but we also shared some of the challenges that we all still face. I do think it’s important to recognise that there’s still work to be done for things to be truly equal.

Consciousness about ocean protection is growing and the members of the media on board were essential to track the stories generated by this kind of work, raising awareness. The role of artists and creative engagement in the issue is so important to bring these topics to new audiences, and we benefitted so much from the perspective of Courtney Mattison and Taylor Griffith, American artists dedicated to ocean protection.

Protecting the ocean in the next 25 years

What ocean do we want to see in 2048? Can we reverse some of the damage that has been caused in recent decades by pollution and overfishing?

What we need is multiple levels of effective ocean protection. We need the vertical protection from the shorelines to the deep sea, we also need the geographic spatial protection as well, andd we need a holistic view of how we’re tackling threats, because issues like climate change, overfishing and plastics all interact with each other. We need a truly global effort to make this happen.

With our work on marine plastics, GCT has moved within five years from working at an island scale to a regional one, with many partners within the Pacific Plastics: Science to Solutions network that we co-developed and run together with the University of Exeter. We are supporting the adoption of a Global Plastics Treaty, with negotiations ongoing until 2024, and we will continue to work with Ecuadorian and UK policy contacts to provide data and stories for compelling case studies to make sure the world takes notice of this problem that has been growing significantly.

On behalf of myself and GCT, I am hugely grateful to have been a part of the Mission Blue expedition, and I would like to thank Alex, Sylvia, Courtney and the team and crew of the Argo vessel and DeepSee submersible, who were wonderful hosts and navigators for an experience that I will surely never forget. I did not think my love for the ocean could get any deeper, but marine life takes on a completely different meaning when you’re with someone like Sylvia.

Can you help us protect ocean biodiversity in 2023?

We are committed to strengthening protection for ocean species in the next 25 years. With your help…

- Salomé and Jenifer are hoping to make their dream of a deep sea species taxonomic guide a reality.

- Diana will recruit local lab assistants to help analyse the environmental DNA samples from this expedition and other sites, and is looking for funding to run the Gills Club, which engages girls in shark science in Galapagos.

- Alex is looking to do an in-depth dive survey study on slipper lobsters.

- Jen can implement plastic footprint surveys across the region.

- Alberto the Waved Albatross will complete the trio of GCT educational storybooks.

Related articles

A week in the life of a female marine researcher

Galapagos and the Antarctic: A look beneath the surface