Whale sharks: perils of the ocean

Whale sharks are among some of the most poorly understood creatures on earth as they spend most of their lives away from coasts and in deep water, inaccessible to researchers.

Whale sharks are among some of the most poorly understood creatures on earth as they spend most of their lives away from coasts and in deep water, inaccessible to researchers. Yet even though we know so little about their life history there is one thing we do know for certain, humans are having a detrimental effect on their global population.

Whale sharks are seen as a delicacy in various Eastern Asian markets, due to the unique nature of their meat, often referred to as ‘tofu shark’.

This highly prized meat goes for huge amounts of money in some areas, with several reports of a single whale shark fin being sold for $15,000, despite being classed as vulnerable since the year 2000 and various countries imposing legal protection over the species.

These fisheries are the biggest threat to whale sharks, not only to the current populations, but future populations as well. It is thought that there is just one global population of whale sharks, therefore fishing in any area for them will cause problems for the whole population, which in turn, could lead to the collapse of the total species population. With their predictable annual aggregations, whale sharks are easy pickings, and this, combined with the long life and slow maturation of whale sharks, could lead to disaster on a global scale. They are thought to live in excess of 100 years, and take over 20 years to mature. This means that in the aggregations where immature males are found, which is almost all of them, and are targeted by fishing operations, the future of the species could be jeopardy, with reduced numbers of males to breed with. This is made worse by the fact it is impossible to set reliable fishing quotas because so little is known about the population structure of these giants.

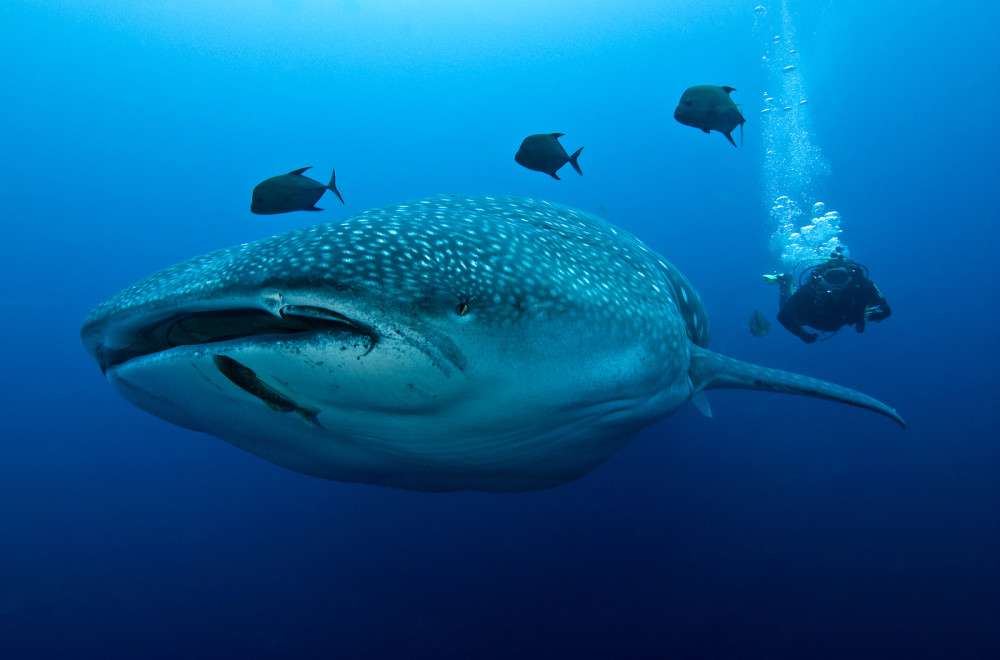

Another threat, albeit on a smaller scale, is boat collisions. These occur because whale sharks spend a large amount of time at the surface feeding. These collisions are rarely fatal but can cause injuries that could impact the rest of their lives.

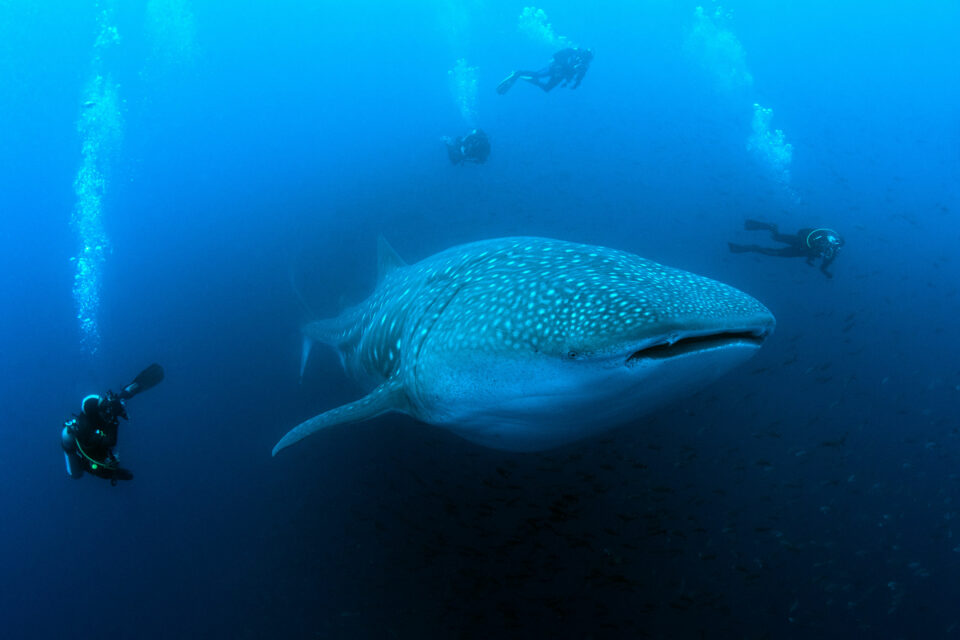

More and more countries, however, are realising their marine life is more valuable alive than dead. The whale shark tourism business alone was estimated to be worth over US$47 million annually over 10 years ago, a figure which has most likely increased as more and more divers are being trained every year (roughly 700,000 a year). This trend towards marine based sight-seeing tourism, if managed correctly, could aid not just the species that people will pay to see, but the entire marine ecosystem.

The Galapagos Whale Shark Project is working to improve our understanding of the Galapagos Marine Reserve’s significance with respect to whale shark migratory patterns, whilst also increasing our knowledge of whale shark migration patterns. Additionally, the project aims to educate local authorities and communities so they can devise effective management strategies for whale sharks around the Galapagos Islands.

The Galapagos Whale Shark Project is working to improve our understanding of the Galapagos Marine Reserve’s significance with respect to whale shark migratory patterns, whilst also increasing our knowledge of whale shark migration patterns. Additionally, the project aims to educate local authorities and communities so they can devise effective management strategies for whale sharks around the Galapagos Islands.

The Galapagos Future Fund provides a platform to support research such as this that is essential to safeguarding the future of the unique wildlife of Galapagos. With your support, we can continue to fund projects to protect endemic species and to investigate the unknown natural wonders of the Archipelago. Please make a donation to the Galapagos Future Fund and in turn make a difference to the future of the whale shark.

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks