The Joy of Poo: Understanding the origin and evolution of Galapagos giant tortoise parasites

PhD student Leandro Patino tells us about his research into the evolution of parasites in Galapagos giant tortoises

The Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoides spp.) is an icon for the unique fauna of the Galapagos Islands and a flagship for Galapagos conservation.

Galapagos giant tortoises inhabit six islands, but some populations are vulnerable to extinction due to the predation of hatchlings and eggs by invasive species such as rats, pigs, dogs and fire ants. Hunting by pirates and whalers together with the mammals they introduced were the main causes of tortoise declines from an estimated 200,000 in the 16th century to around 20,000 individuals in the 1970s. Of 15 (sub)species described originally, five are now extinct.

Increases in the populations of threatened giant tortoises has been achieved through captive breeding programs established in 1965 by the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) and the Charles Darwin Research Station. This management programme involves the captive rearing of hatchlings obtained either from captive parents or from eggs collected in the wild followed by the eventual repatriation of the juvenile tortoises to the wild.

One of the main components of conservation programmes should be the establishment of a baseline for the health status of the species managed, particularly with regard to the presence and distribution of parasites. Since 2004, GNPD has worked with partners from the University of Guayaquil, Concepto Azul (an Ecuadorian social enterprise), the University of Leeds, and the Zoological Society of London, to build disease monitoring and management into their conservation activities. As part of this programme, I am identifying the parasites which naturally infect Galapagos giant tortoises, their importance for the conservation of this spectacular reptile, and how they have co-evolved with their host subspecies.

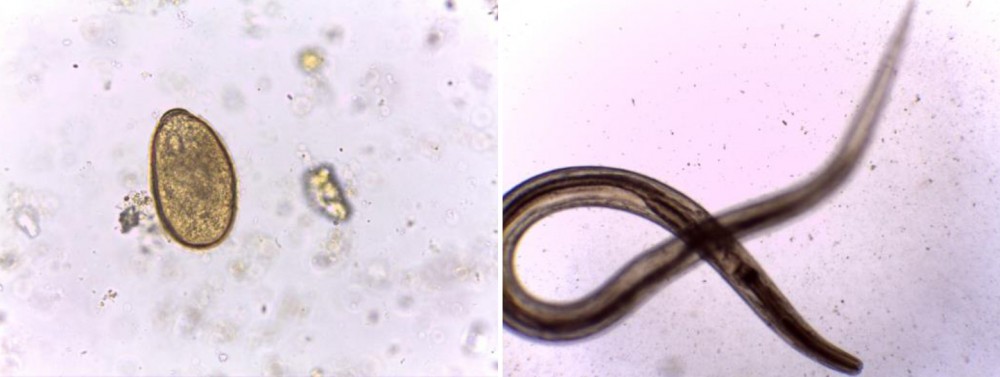

My work is particularly focused on the intestinal worms and blood parasites of giant tortoises. While this may sound somewhat distant from practical conservation, the results are essential for managing the tortoise breeding and reintroduction programmes. It is known that parasites and their hosts co-evolve and form a key component of biodiversity. Thus, it is important to understand and conserve these relationships in order to avoid disrupting interactions that have evolved over millions of years. Also, introducing parasites to new hosts can lead to the development and spread of diseases.

This project has some history behind it. From 2002 to 2007 I worked with the GNPD and the other Ecuadorian and overseas partners to establish the first ever dedicated wildlife disease research laboratory in Galapagos, investigating threats to the endemic fauna of the Archipelago. During this time we identified a blood parasite infecting some of the tortoise species and at least five families of intestinal worms. We also found that tortoises on different islands each had their own unique complements of intestinal worms.

For my PhD research, I firstly collect samples of faeces and blood from giant tortoise populations across the archipelago. I then look at which parasites are present using traditional microscope methods and new approaches based on the latest advances in genetic technology for identifying and quantifying biodiversity. With these new genetic methods I am profiling which parasites are present in the blood and faecal samples from individual tortoises, and looking at the evolutionary relationships between worm species on different islands. Together, this will help us to understand what differences exist in parasite groups across the islands and how they arose. The results will tell us how we should manage our conservation activities to prevent cross contamination of parasites between different host groups. This information is crucial if conservation management programmes are not to disrupt millennia of co-evolution on the islands.

This work is being developed within the University of Leeds (UoL) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and under the supervision of Dr. Simon Goodman – lecturer from UOL, and Prof. Andrew Cunningham – Deputy Head of ZSL’s Institute of Zoology, in collaboration with the GNPD and the Agencia de Regulación y Control de la Bioseguridad y Cuarentena para Galápagos.

Related articles

Galapagos giant tortoises: An update from the field

Meet the six Galapagos species you can adopt with GCT