Global relevance: COVID-19 and sea cucumbers

The brown sea cucumber fishery in the Galapagos Islands was reopened in 2021, six years after it was deemed that the population needed time to recover. After only two weeks it was closed again, with the quota of 600,000 sea cucumbers having been reached by 308 artisanal fishers.

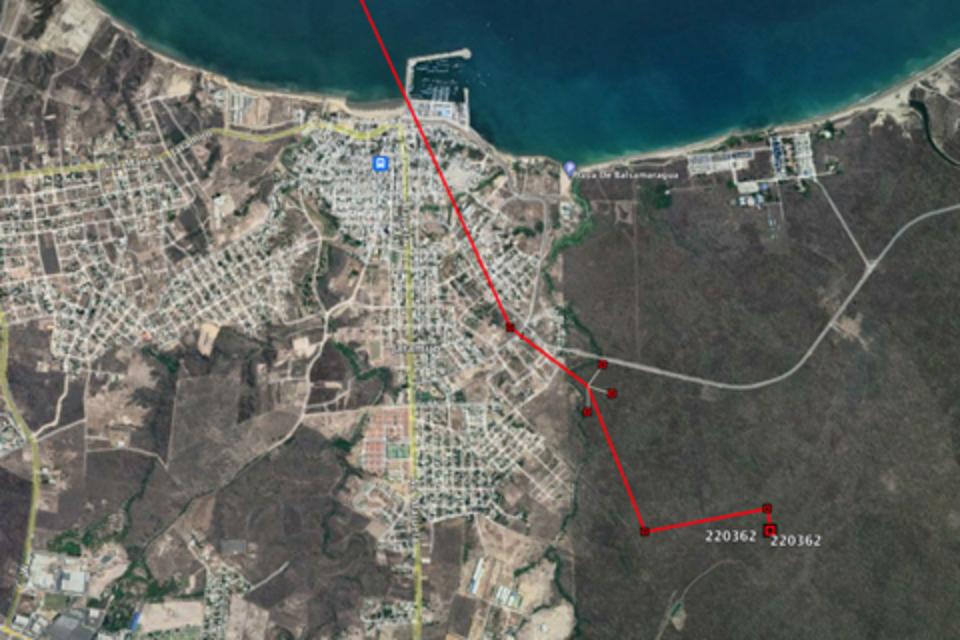

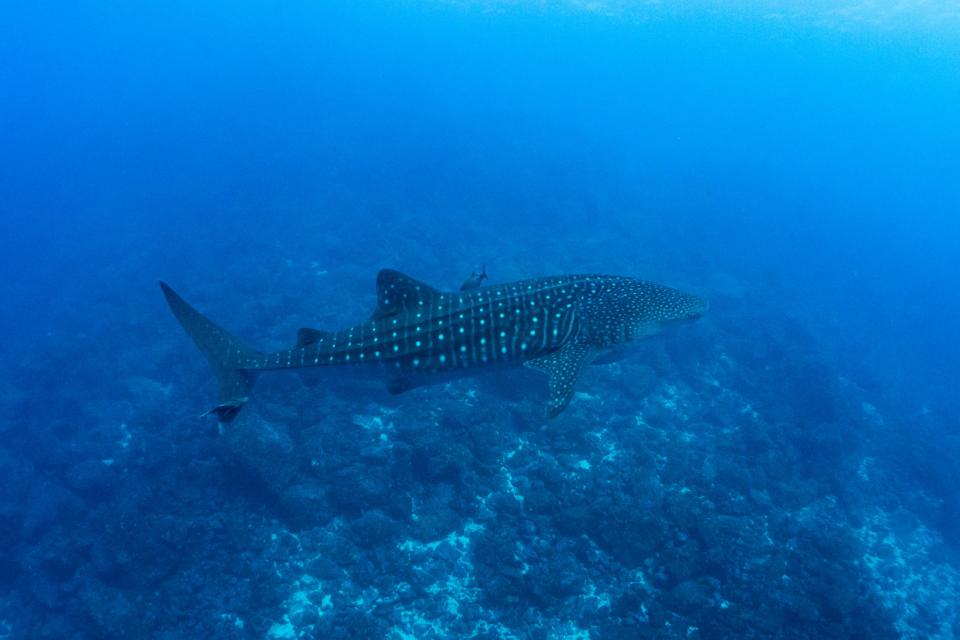

Sea cucumbers are sourced all around the world for the luxury seafood market and traditional medicine use in China. There is no specific species targeted but the size of the animals is often linked to value. In July 2021, the brown sea cucumber fishery in the Galapagos Islands was reopened, six years after it was deemed that the population needed time to recover. After only two weeks it was closed again, with the quota of 600,000 sea cucumbers having been reached by 308 artisanal fishers according to the Galapagos National Park (GNP).

Small-scale fisheries such as those in Galapagos are a vital source of employment, providing income and food for millions of people around the world. Fish and fish products are some of the most highly traded commodities globally, and the disruption to supply chains caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has had severe social and economic consequences. According to the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), major contributors to economic losses for small fisheries in developing countries included the closure of food services and hotel industries in Europe and the USA, the bans on seafood imports to China (for fear of COVID-19 contamination) and the decline in global tourism.

Around the world, the pandemic has had diverse effects on fisheries and other forms of wildlife trade. A recent report by TRAFFIC showed that wildlife trafficking in Asia reduced by 50% in 2020 due to border closures but the online presence of the illegal wildlife trade increased, using social media platforms to advertise their goods. For instance, in February 2021, a team of researchers conducted a monumental review of more than 20,000 social media adverts of wildlife trade in Indonesia and Brazil, and concluded that the pandemic did not decrease the volume of online wildlife trade. Bans on wildlife markets, driven by the suspected COVID-19 origins, could exacerbate the risk of increasing criminal activities related to illegal wildlife poaching and could also affect the livelihoods and food security of billions of people. Thus, some governments have been forced to reopen trade activities in order to supplement the livelihoods of their people.

In Galapagos, the reopening of the longline artisanal fishery and the Endangered brown sea cucumber fishery has been suggested as a reaction to the closure of tourism due to COVID-19. Local fishermen welcomed this decision aimed to ease the economic impact left by the pandemic. However, even after six years, it seems that some populations of sea cucumbers have failed to recover. Some local fishermen reported that they failed to reach their target for the season and recent studies suggest that even long and continuous bans on Galapagos sea cucumber exploitation have failed to allow the populations of this critical marine species to recover. Therefore, it is hard to know whether this decision has provided a viable and sustainable economic solution for the local population.

Chance to build back better

In February 2020, China decided to “ban the illegal trading of wildlife and eliminate the consumption of wild animals to safeguard people’s lives and health”, suggesting positive news for conservation. However, aquatic species do not count in this new legislation due to the view that fishing is a natural resource and a common international practice. Non-edible uses of wildlife such as in traditional medicines are also still permitted. Whilst marine wildlife continues to be seen as inferior to terrestrial species, making progress will be difficult.

For some species, the reduction in industrial exploitation may have kick-started some population recovery. For other species, rapid exploitation may have obliterated entire populations, such as is often the case for sea cucumbers. But as the world continues to reactivate, governments have an opportunity to develop policies that will protect nature and ensure sustainable fisheries into the future.

Part of this must be to understand the true environmental footprint of fisheries and the ecosystem effects of species exploitation. There must also be changes to how many fisheries are managed including ensuring the recognition of equal importance of women’s roles, ensuring their voices are heard in decision-making processes. The fishers of Galapagos have the opportunity to lead the way in small-scale sustainable fisheries as we move through the UN Decade of the Oceans.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 edition of Galapagos Matters.

What can you do to help?

Help us protect Galapagos species by becoming a GCT member for as little as £3 a month.

Related articles

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

Future oceans: Climate change, overfishing and pollution