Giants of Galapagos: Solving the Great Whale Shark Mystery

This is a pivotal time. Together, we can solve the great whale shark mystery.

The Galapagos Islands are a dream destination. For travellers, they are an exotic, remote archipelago. For scientists, they are the spiritual home of evolutionary biology. For explorers, there are still plenty of discoveries to be made. During my visit last month, I had a more specific goal: travel to Darwin Island, in the far north of the archipelago, to find Earth’s largest fish.

The world’s best dive site

We were able to spend three full days at Darwin, enjoying a total of nine dives. The area is beautiful, but that’s nothing compared to what is happening just underneath the surface.

Each dive begins by rolling backwards off a small inflatable boat. Until we hit the water, we don’t know how strong the current will be – it can change dramatically through the day – so we immediately fin down to a rocky ledge on the wall. If there is a strong current, we find a spot on the reef, hang on, sit tight and wait. I like to wedge myself between a couple of rocks and enjoy watching life pass me by – literally.

This is an awe-inspiring place. I saw hundreds of hammerhead sharks, Galapagos sharks, yellowfin tuna, sea turtles, huge schools of fish… on every dive. It’s easy to understand why Darwin is routinely rated as the world’s best dive site.

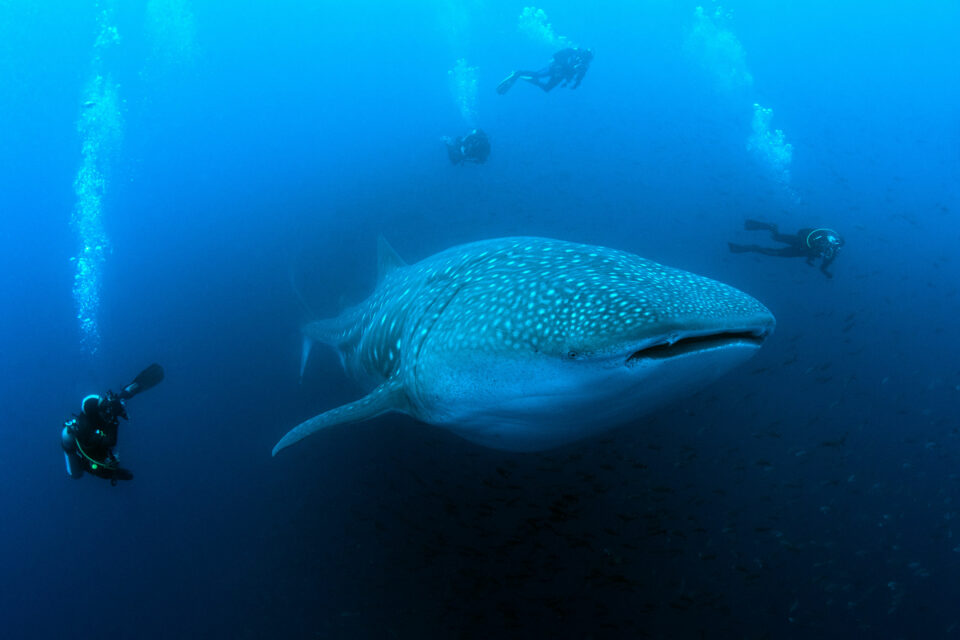

As I was on my safety stop on the last dive of the first day, I finally saw it. The largest fish I have ever seen. It was a colossus, around 16 m long!

Introducing… the whale shark

Whale sharks are enigmatic. When you realise just how gargantuan they actually are, that becomes hard to understand. An average school bus is up to 14 m long and 16 tonnes in weight. The largest measured whale shark was 20 m long, and they reach at least 34 tonnes. They are very, very big. Despite that, they were only discovered by science in 1828 and, until the 1980s, there had only been 320 documented sightings around the world. Even Jacques Cousteau, for all his ocean exploration, only saw two in his life.

Knowing this, imagine my colleague Jonathan Green’s surprise when he saw whale sharks as soon as he started diving at Darwin. That was back in 1988. Jonathan, an earth scientist and guide who had only recently arrived from the UK, quickly realised that almost nothing was known about these ocean giants. He became determined to learn more.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t easy. Darwin Arch is slightly over 320 km north of the main port in the islands, which itself is over 1000 km from the South American mainland. There is no landing available on Darwin, it’s expensive to get to, and the dive site is frequently exposed to rough seas and strong currents. Also, the sharks are only seasonally present, from around July to October. Despite these challenges, Jonathan persevered.

In the meantime, scientists – including myself – have learnt a lot more about whale sharks. It turns out they are not secretive, just very focused on their needs. A huge fish needs a lot of food, and their usual prey – zooplankton – are sparse in tropical waters. To cope with that reality, the sharks aren’t evenly dispersed. They purposefully time their movements to coincide with regional explosions in productivity, such as huge plankton blooms or fish spawning events.

We have now found several places in which they can be found fairly routinely. In many of these areas, tourism industries have sprung up to allow people to swim with the sharks. They are completely harmless to people, so hundreds of thousands of people have now had the opportunity to view them in the wild.

The whale shark mystery

Of course, there is a catch. All of these areas, across the world, share a common denominator: most of the sharks present are juvenile males. I help to oversee the scientific program for the global whale shark database and, looking at the full library – over 5700 sharks from 45 countries – a full 71% are males. Almost all of these are juveniles between four and nine metres in length. Somehow a lot of very large, very small, and very female sharks are being missed. They are the dark matter of the oceans.

To put this in personal perspective, I have been studying whale sharks since 2005. I have worked extensively on the species in all three tropical oceans. Before the Galapagos, I had never seen a shark over 10 m long, even though they are known to reach twice that size. In many countries, adult females have never even been recorded. They are very, very difficult to find.

This is what I call the great whale shark mystery. Where are all the females? Where are the adults (and babies) of either sex? Following years of concerted research effort, and a huge number of divers and photojournalists exploring the furthest reaches of the world, we still can’t answer these questions.

If only this was purely a curiosity-driven conundrum. Whale sharks are one of the most threatened of all fish. Based on the current global IUCN Red List assessment, fishing and other human pressures have at least halved their population over the past few decades. In some areas sightings have declined over 80%.

To save the whale shark, we need to find the females, locate where they go to breed, identify the main human threats, and remove them. Fast.

Whale sharks in Galapagos

To get these answers, we have to return to Jonathan and his sharks. Darwin Arch is even more special than he first realised. Almost all of the sharks seen here are females. Indeed, Jonathan has only ever seen two males here. Most of the sharks are adults. And almost all of them… are pregnant.

Female sharks are the most important part of the population, because they produce more sharks! In conservation terms, the very best group to focus on are the large juvenile and young adult females. Most baby sharks probably don’t survive to adulthood due to predators or other factors, but these larger juveniles have a high chance of a long life – and their whole reproductive lifespan is ahead of them. Specifically removing threats to these medium-sized females will help the species to recover as quickly as biologically possible.

At this stage we know very little about whale shark reproduction. Only one pregnant whale shark has ever been physically examined by scientists. This singular shark, caught in a fishery off Taiwan in 1995, carried over 300 pups inside her. That’s almost twice as many as any other shark species. We don’t know if this is normal. Given that this shark was ‘only’ 10.6 m long, it may well be a small litter for whale sharks. We don’t know how old they are when they become adults, or how often they reproduce. The Galapagos offers the best – and at this point, only – opportunity to learn more.

Thanks to the support of the Galapagos Conservation Trust and other funders, Jonathan and his colleagues have been able to start deploying satellite tags to follow the movements of these pregnant sharks. They are true ocean wanderers. One shark travelled almost 7000 km over five months before the tag detached. The limited data they have been able to gather to date has provided intriguing insights into their lives.

Solving the mystery

There are several key questions we need to answer so that we can effectively protect whale sharks:

- How many sharks swim past Darwin?

- What proportion are pregnant?

- How often do they come back?

- Where have the sharks come from?

- Where do they go after Darwin?

With that information, we will know which threats may be affecting them, the habitats that need increased protection, and where to look for the female sharks in other oceans. We will also be able to find out how often they have pups. That allows us to calculate how quickly fisheries can reduce their populations, and how fast the species can bounce back once human threats are removed.

We have the ability to answer these questions in the next 3-5 years. We can deploy the latest satellite tag technologies to track the movements and behaviour of the sharks after they leave the archipelago, and analyse skin samples to identify where they’ve travelled from. To achieve this, we need new supporters who want to join the team and contribute the vital resources we need to fund this ground-breaking work. If this sounds like something you would like to be a part of, we would love to hear from you.

In addition to supporting dedicated scientific expeditions, there is another way we need your help. Have you, or any of your friends, seen a whale shark in the Galapagos? Each and every whale shark has a distinct pattern of spots, making them individually recognisable. By collating photographs of whale sharks from the Galapagos, we can work out how many sharks travel through this area, and how often they’re coming back. If you do know of any photos, please get them submitted to the global whale shark database.

This is a pivotal time. Together, we can solve the great whale shark mystery.

Jonathan and Simon gratefully appreciate the Galapagos National Park authorities granting them permission for this trip. This photographic expedition was sponsored by a grant from the GLC Charitable Trust to the Marine Megafauna Foundation, and supported by the Galapagos Conservation Trust. Thanks to the crew of the Queen Mabel for all their assistance.

Related articles

Ocean Protection Webinar 2023

Tagging a new constellation of whale sharks