Sharks of Galapagos

Read about the sharks of Galapagos in this article originally written for the Shark Trust's magazine Shark Focus.

“The Bay swarmed with animals; Fish, Shark & Turtles were popping their heads up in all parts.” Charles Darwin made this entry into his diary on 17th September 1835 having just moored in St Stephen’s Harbour on the island that is today known as San Cristobal in the Galapagos Archipelago. Having been travelling on board the HMS Beagle for almost four years by this point, his description provides an interesting insight into how notably abundant the marine life was around these isolated volcanic islands at the time of his visit.

Located in the eastern Pacific 1,000 km from the coast of mainland Ecuador, the waters around the Galapagos Islands continue to host an impressive array of species, albeit in lesser quantities than during Darwin’s stay. The unique convergence of cold, nutrient-rich currents with warm, tropical waters which occurs around Galapagos has resulted in tropical, temperate and cold-water marine species surviving in relatively close proximity. The difference in sea surface temperatures across the archipelago can be as much as 13⁰C, so whilst tropical fish swim around coral reefs off some islands, Galapagos penguins hunt cold-water sardines off others less than 100 km away.

Galapagos Sharks

At least 58 species of elasmobranch have been recorded in Galapagos waters, including 33 species of shark, 19 species of ray, four skates and two chimeras. That’s not to say that more don’t exist: as recently as 2012 a brand new species of deepwater catshark (Bythaelurus giddingsi) was described from several specimens caught around Galapagos by the California Academy of Sciences. Several other species that are assumed endemic are similarly known from only a handful of specimens, for example the Galapagos grey skate and the deepwater chimaeroid commonly known as the Galapagos ghostshark.

As is often the problem with common names and their implied associations, one species that bears the Galapagos preface is not exclusive to the Islands. The Galapagos shark is in fact widespread, occurring around islands in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The name in this case derives from the first specimen to be scientifically described which was caught in Galapagos in 1905.

Of all the sharks in Galapagos however, one species sticks out as being the most sought after by visitors: the charismatic scalloped hammerhead. The best chance for hammerhead sightings in Galapagos is around the northern-most islands of Wolf and Darwin during the warm season (Dec-May), where schools of these iconic sharks, sometimes over 100-strong, can be seen swimming in vast circles. Galapagos is one of the few remaining places on Earth where such schools can be observed, although the reason behind this gregarious behaviour is still debated.

Tagging studies have revealed a high degree of connectivity between eastern Pacific populations of scalloped hammerheads, with evidence of individuals travelling between the protected waters of Galapagos, the Cocos Islands in Costa Rica and Malpelo Island in Columbia. Discovering that hammerheads, as well as other large marine pelagics such as other shark species and turtles, have been found to travel between these areas has led to discussions of creating a protected Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor to ensure that protection for these species extends to their full range. However, tangible legislation is still to be achieved.

Shark Protection

Given the proliferation of sharks in Galapagos, it is unsurprising that the archipelago has a relatively long and tainted history of shark fishing. The industry first became a commercial enterprise in the Islands in the 1950s and it has been growing ever since. It is estimated that over 100,000 tonnes of sharks haven been taken from Galapagos waters by the Ecuadorian fleet since 1950. When you take into consideration the countless boats from other countries such as Costa Rica, Columbia and Japan, which are also known to fish for sharks in Galapagos, the reality of human impact on the marine ecosystem becomes devastatingly apparent.

In response to this situation, the Ecuadorian authorities have, over the past 20 years, brought in various laws and regulations which afford sharks some protection. In 1998 the ‘Special Law for Galapagos’ was passed, laying out a legal framework for certain aspects of island life including fisheries management. This meant that the 133,000 sq. km Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) could be created and given national protected area status. Commercial fishing, including shark finning and long-lining, was prohibited and the Special Law meant that the Galapagos National Park (GNP) authorities had a legal backing for enforcing Reserve regulations.

In 2004, further protection for sharks was granted for the GMR after the President of Ecuador signed a decree outlawing the export of any shark products. This put the nation at the forefront of global shark conservation on paper but it is questionable how effective it was in reality. Shark fins continued to be exported from the mainland by falsely labelling them as ‘plastic sheeting’ or by smuggling them into Peru. Unfortunately, the legislation was amended by the President in July 2007 to the effect that fisherman are now allowed to extract and export fins from sharks which are ‘incidentally’ caught during regular fishing activities. Given that shark bycatch can account for up to 70% of the total catch2, this loophole is now being actively exploited without any legal repercussions and a commercial export market is once again in full swing.

That said, legal action is still taken against boats that fish illegally within the GMR. Between 2001 and 2007 the GNP authorities apprehended 29 illegal shark catches, and in 2011 a vessel containing 379 shark carcasses was seized, impounded, and the 30 crew members put on trial. Unfortunately, an issue within the judicial system meant that this case was eventually annulled.

Whilst certain types of fishing remain banned within the GMR, the GNP has, on several occasions over the last decade, been seen to trial prohibited fishing techniques. Whilst this sounds concerning, in a press release sent out by the GNP in 2014, they said the reason behind this was that “it is the responsibility of the state to carry out scientific study into all methods of fishing including those not permitted. This is due to technological advances allowing for improved capture accuracy which will improve the quality of life for local fisherman.” A pilot study of long-line fishing conducted by the GNP in 2003/4 found that bycatch rates were between 35-78% which led to them rightly declaring that it would remain illegal within the reserve.

Uncovering Hidden Secrets

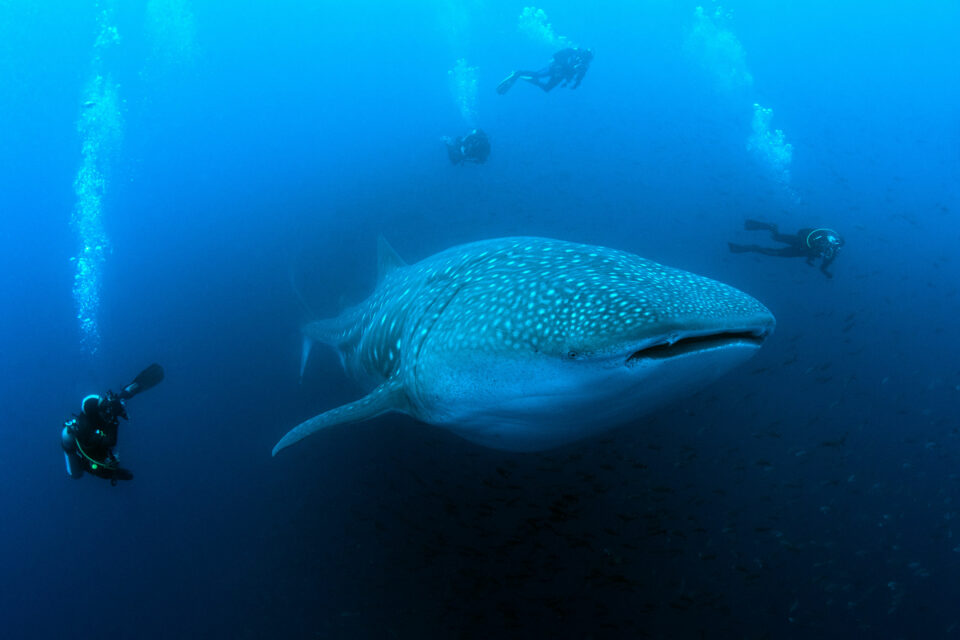

Another significant visitor to the archipelago is the enigmatic whale shark. In Galapagos, whale sharks are regularly sighted around Darwin and Wolf between the months of June and September. The aggregations are like nowhere else on Earth.

Jonathan Green, a British naturalist, photographer and diver, began guiding expeditions to Galapagos in the late 1980s. As time progressed he realised that whale sharks seemed to appear on a seasonal basis in the north of the archipelago, but it was a little while longer until he realised the importance of the sharks passing through.

Unlike aggregations in many other locations around the world, which are largely made up of immature males, it became apparent to Jonathan that the majority of whale sharks sighted in Galapagos were large mature females. Not only this, a very high proportion of the females had swollen abdomens, suggesting that they were in an advanced stage of pregnancy. Given how little is known about whale shark reproductive ecology, this was an exciting discovery, and one that spurred Jonathan into founding the Galapagos Whale Shark Project (GWSP).

In 2011, the inter-institutional GWSP research team began an ambitious study to tag and track whale sharks that passed through the GNP. In their first year, they tagged 24 individuals which at the time represented the single largest tagging study of the species ever undertaken. Several interesting patterns began to emerge from the tracks of these sharks. Firstly, it was seen that individuals only remained within the protected waters of the GMR for several days, appearing to use the islands as some kind of way-marker on a large-scale migration. Secondly, it was observed that sharks would continue past Galapagos into the open ocean early in the season, but move back towards the continental shelf later in the year.

In 2012, they continued to tag sharks and it now looks likely that a predictable migratory corridor exists. Why the sharks are showing this movement pattern has still to be established, but a third tagging study, conducted in August 2014 thanks to funding from the Galapagos Conservation Trust, hopes to provide further insight. Not only will the tracks add to the body of evidence for an inter-annual migration path, but the team have also attached a different type of tag onto several individuals which will measure their vertical movements as well as horizontal. Interestingly, one shark which was seen on this latest trip has been observed in three consecutive years and each time she has appeared to be heavily pregnant.

Whether or not the elusive breeding grounds of the world’s largest fish are indeed located near the Galapagos Islands is still to be determined. It will need persistence, use of cutting-edge technology and a significant amount of funding to establish if this is the case, but one thing for certain is that the GMR acts as an important stopover for breeding individuals.

Given its history and association with ground-breaking theories in the past, it seems very apt that the Galapagos Islands still play a central role in uncovering some of the mysteries of our natural world. Who knows what discoveries will emerge from this incredible archipelago next.

‘Sharks of Galapagos’ was originally published in Shark Focus, the magazine of the Shark Trust.

References

1. Darwin, C. (1988) Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary. Cambridge University Press.

2. Schiller, L., Alava, J.J., Grove, J., Reck, G. & Pauly, D. (2014) The demise of Darwin’s fishes: evidence of fishing down and illegal shark finning in the Galapagos Islands. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. Published online in Wiley Online Library. DOI: 10.1002/aqc.2458

3. Jiménez-Uzcátegui, G., Ruiz, D., Snell, H. L. (2011) CDF Checklist of Galapagos Terrestrial & Marine Vertebrates – FCD Lista de especies de Vertebrados terrestres y marinos de Galápagos. In: Bungartz, F., Herrera, H., Jaramillo, P., Tirado, N., Jiménez-Uzcátegui, G., Ruiz, D., Guézou, A. & Ziemmeck, F. (eds.). Charles Darwin Foundation Galapagos Species Checklist – Lista de Especies de Galápagos de la Fundación Charles Darwin. Charles Darwin Foundation / Fundación Charles Darwin, Puerto Ayora, Galapagos: http://www.darwinfoundation.org/datazone/checklists/vertebrates/ Last updated 18 Mar 2011.

4. McCosker, J.E., Long, D.J. & Baldwin, C.C. (2012) Description of a new species of deepwater catshark, Bythaelurus giddingsi sp. nov., from the Galápagos Islands (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae). Zootaxa 3221: 48-59.

5. McCormack, C. & Kyne, P.M. (2007) Rajella eisenhardti. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 25 September 2014.

6. Kyne, P.M., Valenti, S.V. & Barnett, L.A.K. (2007) Hydrolagus mccoskeri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 25 September 2014.

7. Peñaherrera, C., Ketchum., J., Espinoza, E., Hearn, A. & Klimley, P. (2011) Hammerhead sharks of Galapagos: their behaviour and migratory patterns. Galapagos Report 2009-2010.

8. Jacquet, J., Alava, J.J., Pramod, G., Henderson, S. & Zeller, D. (2008) In hot soup: sharks captured in Ecuador’s waters. Environmental Science 5(4): 269-283.

9. Carr, L.A., Stier, A.C., Fietz, K., Montero, I., Gallagher, A.J. & Bruno, J.F. (2013) Illegal shark fishing in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy 39: 317-321.

10. Parque Nacional Galapagos (2014). MAE trabaja con sector pesquero en Galapagos. Boletín de Prensa No. 080 (09/08/2014).

Related articles

Galapagos marine reserve expansion brings hope - but new management challenges

World Oceans Day 2022: Tagging Ocean Giants