Garbology: new perspectives on waste

by Professor John Schofield On a remote beach on San Cristobal, there is a plastic bottle. Inside the bottle, there is a toothbrush. How did it get there? What is its story?

On a remote beach on San Cristobal, there is a plastic bottle. Inside the bottle, there is a toothbrush. How did it get there? What is its story?

It is estimated that nine million metric tonnes of plastic enter the oceans every year, floating around the globe on ocean currents or gyres. It is only recently, however, that scientists working in Galapagos, led by my team from the University of York, have engaged in ‘garbology’, treating marine plastic as archaeological artefacts.

The study of rubbish has a curious origin. In 1970, the American journalist A.J. Weberman began rifling through Bob Dylan’s dustbins, hoping to find clues t hat would shed light on his music. This questionable practice, which Weberman referred to as ‘garbology’, took on a more respectable guise a few years later when University of Arizona archaeologist William Rathje began the Tuscon Garbage Project, using the contents of household waste to explore patterns of consumption. “In the three or so million years of humankind, we have never had more reason than we have today to try to understand our relation to our artifacts – what we manufacture, use, and discard – and how our artifacts both mirror and shape our actions and attitudes,” he wrote in 1984. For Rathje, the examination of humans through their rubbish was not only a scientific project but also one with profound moral and political significance.

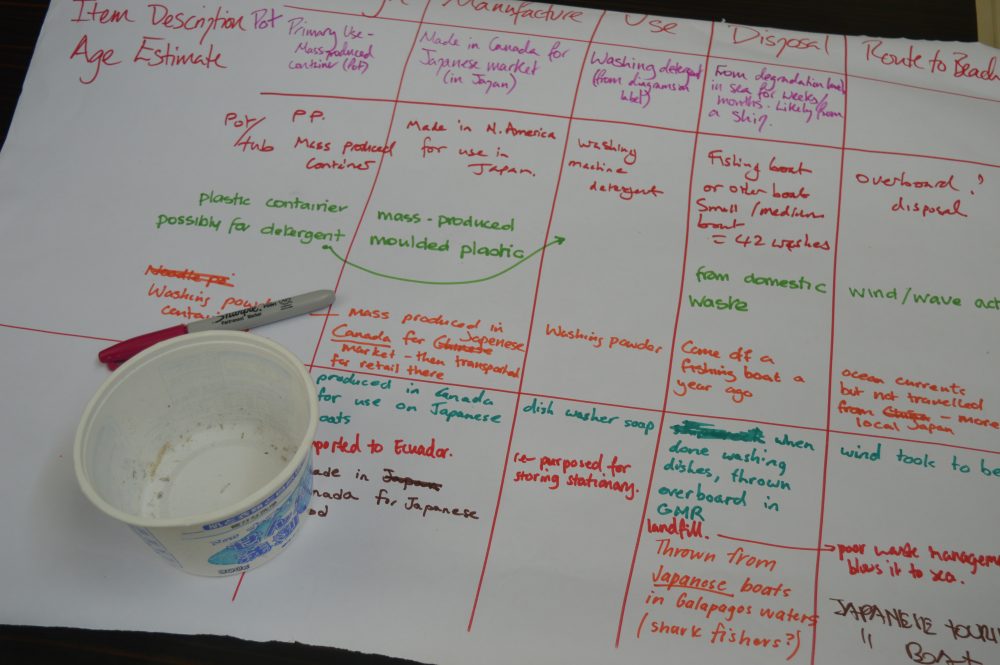

Several research groups with an interest in Galapagos are following in Rathje’s tradition. In a recent study, Dr Erik van Sebille and colleagues at the University of Utrecht studied ocean currents to reveal that most of the plastic reaching Galapagos has come from Southern Ecuador and Northern Peru. In recently published work in the journal Antiquity, we have been particularly interested in exploring the stories of plastic objects that have turned up in Galapagos. In May 2018, as part of GCT’s Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos programme, we took part in a ‘Science to Solutions’ workshop (run by the Galapagos National Park and GCT and hosted by the Galapagos Science Center and Charles Darwin Foundation) to develop and test a methodology for collecting the narratives of discarded objects.

This work – and that of others – expanded the scope of archaeology from its more familiar focus on the deep past to what is now referred to as contemporary archaeology, the application of archaeological methods to the period of living memory. After all, most ancient archaeology involves the scientific analysis of people’s rubbish, objects discarded as no longer useful that turn up thousands of years later. In the case of contemporary archaeology, the time that elapses between the use of an object and its discovery is just much shorter, usually a matter of years but sometimes days.

In every story human actions were the likely cause of pollution, reinforcing the central message that actions have consequences.

We chose Bahia Rosa Blanca as our study site, a remote beach on San Cristobal that can only be accessed by boat, has rarely been cleaned and had therefore accumulated a wide range of objects, such as plastic bags, Styrofoam cups, flip-flops, the sole of a shoe, a pot of detergent, hats, Lego, dolls, fishing gear and the bottle with a toothbrush inside. Back at the Galapagos Science Center, we grouped the artefacts and identified eight whose stories we were to explore in more detail.

Story-telling is central to archaeological interpretation. We speculated on the objects’ life stories based on the evidence available to us, and created stories around each of them. Were the items lost or discarded locally, or had they travelled longer distances? Did traces of their use give a clue to their origins? Did evidence of weathering or the colonisation of marine species suggest how long items had been either at sea or on the beach before we collected them? How fast were they degrading? In every story human actions were the likely cause of pollution, reinforcing the central message that actions have consequences.

Of all the objects, the bottle containing the toothbrush produced the most interesting stories. Some imagined the toothbrush to have been the property of a fisherman, who had used the plastic water bottle to keep it clean whilst at sea.

But when the cap was unscrewed and the contents gave off the smell of methylated spirits, the message in the bottle changed. Rather than being used on teeth, the brush became reimagined as a repurposed boat-cleaning tool that had been swept overboard in a storm.

standard wear patterns (right). (Analysis and illustration © Sean Doherty)

We believe ‘garbology’ has an important role to play in creating novel ways of mitigating marine plastic pollution. Set within the context of storytelling in co-creative and community-led conservation practice, objects become vital as things to tell stories with or about or to narrate meaning through. Alongside beach-cleans, policy-making and recycling initiatives, human behaviours remain central to reducing marine pollution. The work being undertaken in Galapagos could provide a novel and effective solution, not just locally but on a global scale.

This article was orginally published in our Spring-Summer 2020 issue of Galapagos Matters.

What can you do to help?

Please help us tackle plastic pollution today by giving a donation or joining up as a GCT member.

Related articles

New research shows that Galapagos giant tortoises are ingesting plastic waste

Creating a circular economy for plastics in Galapagos