Future oceans: Climate change, overfishing and pollution

Climate change is probably the single biggest threat facing the world’s biodiversity. If humans continue to live as we do today, rising temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events will cause widespread extinction.

Climate change is probably the single biggest threat facing the world’s biodiversity. If humans continue to live as we do today, rising temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events will cause widespread extinction. Whilst most policies created by world leaders focus on the crucial goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, we must also protect the natural ecosystem services that are already combatting climate change.

One of the key goals of the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in November 2021 was to ‘protect communities and natural habitats.’ Preserving ecological integrity gives populations and communities a greater chance of withstanding the impacts of a changing climate. This, in turn, will protect local communities and livelihoods. We know that climate change is already having an impact on a range of terrestrial species, affecting the food availability, nesting success and habitat structure of animals like the giant tortoise. Marine species will be affected too, with consequences for fish, sharks, turtles and seabirds like penguins, the flightless cormorant and the boobies that depend on the resources of the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) for their survival. If stress on the GMR continues, it will inevitably impact the productivity of Ecuador’s commercial fisheries.

The Galapagos Marine Reserve

The Galapagos Marine Reserve was created in 1998, largely due to concerns about the impacts of long-line fishing and decreasing fish stocks. At that time, covering an ocean area of 133,000 km2, it was the second-largest marine protected area in the world. Today there are many reserves that are larger, though the GMR remains a protected area of global importance. Upwellings of nutrient-rich water around Galapagos support an abundance of marine life. This attracts vast industrial and artisanal fishing fleets to the region, including Ecuadorian vessels using nets or long-lines, as well as ships from elsewhere in the world.

Models produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2019 indicate that although climate change will likely result in a reduction in fishing catch around Galapagos over the next 40 years, it will probably not be as severe as in the rest of the Eastern Tropical Pacific region, such as along the coast of South America. Therefore, as climate change and overfishing contribute to the collapse of fish populations elsewhere, there has been and will continue to be an increase in the fishing intensity surrounding the relative sanctuary of the GMR. Fisheries act as contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions and cause a myriad of environmental impacts throughout the entire supply chain, but these impacts have not been comprehensively investigated.

Plastic pollution is also a problem in the fight against climate change. According to a report by the Center for International Environmental Law in 2019, greenhouse gases are emitted at every stage of the plastic lifecycle from extracting fossil fuels to managing plastic waste. The report says that in 2019, the global production and incineration of plastic was estimated to produce more than 850 million metric tons of greenhouse gases – the same as 189 huge 500-megawatt coal-fired power stations. In addition, early evidence suggests that plastic at the ocean’s surface continues to release methane and other greenhouse gases, which increases as the plastic breaks down further. There are also worries that microplastics in the oceans may affect the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide.

Protecting Galapagos’ species

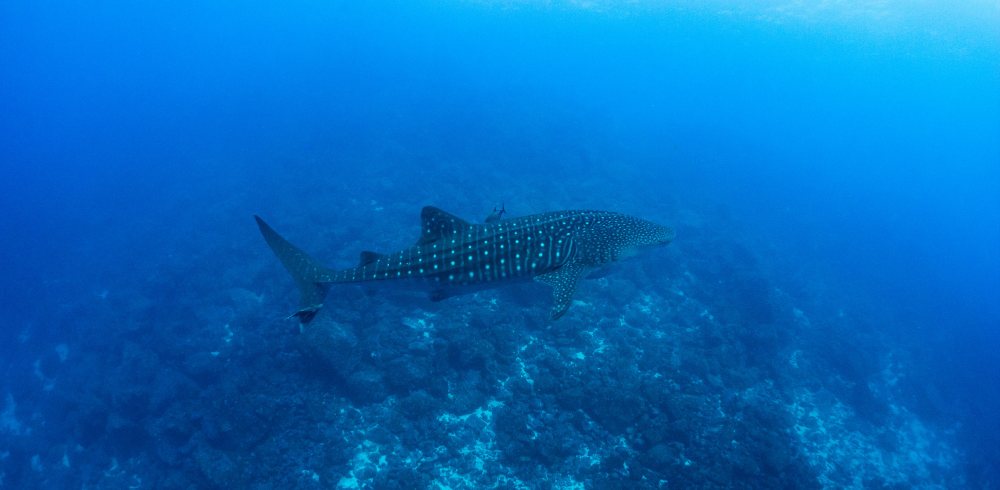

Sharks play an important role in keeping our oceans ecologically balanced and able to act as an effective carbon sink. Conserving sharks, therefore, has important implications for mitigating climate change as well as sustaining essential ecosystem services and livelihoods for coastal communities. However, although Ecuador does not formally recognise a shark fishery, the artisanal long‑line fleet continues to land more than 250,000 sharks every year and simply declares them as ‘bycatch’.

GCT is working with its partners to provide the evidence needed to create new marine protected areas beyond the current boundary of the GMR, including vital migratory corridors through the Eastern Tropical Pacific. This should benefit important marine wildlife as well as fisheries both within the GMR and outside its border. However, this has been met with strong resistance from some groups within the Ecuadorian fleet as it undertakes more than 20% of its activity within Galapagos’ exclusive economic zone. A better dialogue is needed to explore new opportunities, such as economic incentives for sustainable fishing through certification schemes and beneficial supply chains.

It is of vital importance to GCT that we reduce the destructive impact of climate change on the Islands’ unique and vulnerable species whilst supporting sustainable livelihoods in Galapagos.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 edition of Galapagos Matters and slightly adapted for this blog.

What can you do to help?

GCT is working towards a more sustainable vision for the GMR. We want to increase the resilience of the Galapagos artisanal fishery to the threats of climate change and marine plastic pollution. By protecting the environment, we can help to stabilise climate change and, in turn, protect the wildlife of Galapagos, local livelihoods and the ecosystem services needed by the international community. Please donate to GCT today.

Related articles

Climate change and plastic pollution: the inextricable link

Santa Cruz: The Evolution of the Agricultural Zone