Finding the solution to plastic pollution

Jen Jones, GCT's Head of Programmes, explains her PhD research and what we have learned from our Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos Programme so far.

Have you ever been swimming in water that rattles due to the plastic floating in it? I have, in a small bay on the eastern coast of San Cristobal island, a place that hosts a wealth of endangered species including Galapagos green turtles and sea lions.

That was probably one of the most profound moments for me during the last three years whilst completing my PhD research, investigating the impacts of huge privilege doing research in this special place after many years working at GCT, trying to add a little piece of knowledge to our collective efforts to reduce the problems of plastic waste accumulating in the natural environment.

During this study, I have counted and categorised more than 10,000 pieces of plastic in the quest to trace the source of pollution we find in Galapagos. I have worked with more than 50 dedicated high-school and university students to find out if citizen science can be part of the solution to monitor plastic pollution over time. I have also been pooed on by a marine iguana, have patiently waited for a sea lion to stop her game with our snorkel survey transect tape, and have spent more hours than I care to remember painstakingly sieving sand in the scorching equatorial sun to extract tiny microplastics from the sand.

I’ve often heard people talk about how little the Galapagos Islands have changed since Charles Darwin’s visit with the HMS Beagle crew back in 1835. The major caveat that tends to come with that statement is “well, except from the plastic that is!”.

This rainbow of plastic pieces, my study species if you will, is a visible sign of our global consumerism. Coming in all shapes and sizes, this anthropogenic signature is littered around coastlines with an erratic distribution. In some bays, there is a staggering amount of plastic accumulated (such as the one with the rattling water), whereas others, just a kilometre away, are completely pristine with no accumulation happening.

Tracing the sources and drivers of this plastic waste, defining the impacts on wildlife and society, and implementing solutions are the key elements of GCT’s Plastic Pollution Free Galapagos programme. A lot has happened in the last three years since our first ‘Science to Solutions’ workshop in Galapagos when we mapped out our major knowledge gaps with researchers, managers, business owners and community groups. Here is a summary of what we have learned so far:

The majority of plastics we find on remote beaches are floating into the Galapagos Marine Reserve on ocean currents.

Oceanographic models show that floating plastics that reach the Islands from continental South America are most likely to be entering the ocean in mainland Ecuador or Peru. There is very limited current flow to the Islands from the west; plastic entering the ocean here is more likely to be carried out to the great oceanic gyres (plastic garbage patches), transported away from the Islands due to the upwelling. We also know that marine industries, such as industrial fishing, contribute a significant proportion. What that proportion is is too early to say with any certainty, but it is likely to be at least 30%.

Like most places, there are still local inputs of plastic pollution in Galapagos.

Street litter data show that plastic pollution – such as cigarette butts, food wrappers and construction waste – increases as you get further away from the sea, and microplastics are found in higher densities in seawater around the harbour in San Cristobal, suggesting that it has come from local sources such as wastewater (e.g. microplastic fibres from laundry).

The composition of plastic pollution on beaches is highly variable.

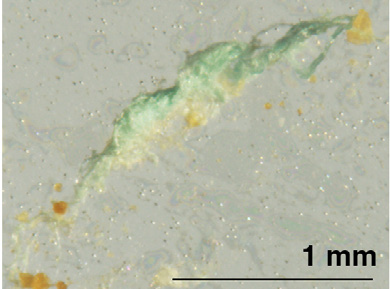

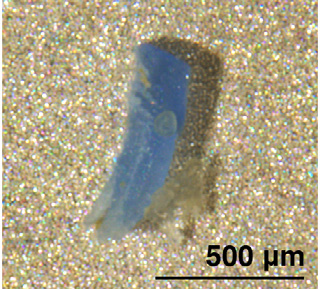

Most of the plastics we find are fragments, suggesting that plastic items are breaking down on the beaches, perhaps speeded up by the high UV radiation (which breaks down plastics) on the equator. Over 20% of the identifiable items we find are linked with the drinks industry, with plastic bottles, lids and bottle rings very commonly found across all the islands that we collected samples from. Ropes are the next most common item group and toothbrushes, pens and food containers follow closely behind.

Animals are consuming microplastics but harm is currently unknown.

We sampled seven species of marine invertebrates for evidence of microplastic ingestion. These included oysters, urchins, sea cucumbers, snails and barnacles. All of these species interact differently with their habitat and have different feeding habits. For example, some are filter feeders, consuming particles from the water column whilst others are grazers, scraping hard surfaces to eat films of algae. The fact that microplastics were found in all of them suggest that there are many ways that plastics can enter the food web. Although we know that these animals are consuming microplastics, we do not yet know what harm this is causing. In lab studies with other marine species, we know that microplastic can accumulate inside the body and can reduce the fitness of animals, affecting feeding and reproductive health. The solution here is to reduce microplastics leaking into the environment (e.g. by better filtration in water treatment plants) and to take larger plastics out of the system before they disintegrate into microplastics.

We know that more than 30 different marine vertebrates have been entangled in plastic waste.

Photographic evidence showing injuries caused by plastics to wildlife such as sea lions and turtles demonstrates the need to remove these items from the environment. Clean up of plastics from beaches must continue whilst we are working on longer term solutions to reduce the use of plastics.

We have identified the tools needed to support management and monitoring of plastics – and citizen scientists are key.

A combination of oceanographic models, drone surveys and beach survey procedures are being developed into a toolkit that is already being followed in the Cocos Island National Park, Costa Rica. We are not far from being able to predict where and when the plastic arrives, and therefore remove it quickly. This will lower the risk of entanglement or ingestion by animals and prevent the formation of microplastics which are impossible to remove. Citizen scientists help us to sample plastics in more places over longer time periods, either collecting data themselves from their local areas or by helping to analyse photographic data online.

There is strong motivation at every level to act on plastic waste in Galapagos.

There are more than 25 community initiatives in Galapagos promoting clean ups, selling products made from up-cycled plastics, and zero waste shops. At a political level, plastics and waste management are important elements of the Galapagos 2030 Plan, recently released by the Governing Council of Galapagos to lay out the blueprint to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. In addition to this local support, international tourism businesses are also keen to hear recommendations to improve their sustainability.

|

|

To move from science to solutions, we must work at a regional level.

In 2021, in partnership with the University of Exeter and 17 regional partners, we launched the ‘Pacific Plastics: Science to Solutions’ network to build the foundations we need to amplify our plastics work to the scale required.

Conclusion: We can’t stop now.

Great progress has been made in the fight against plastic pollution in Galapagos but the problem on a global scale is continuing to grow, not least due to the increase in single‑use plastics and reduction in funding for waste management during the COVID-19 pandemic. To make an impact in the long term, we must continue to work on reducing the pressure on our oceans in a holistic way. We need you to join us on this journey!

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 edition of Galapagos Matters and slightly adapted for this blog.

What can you do to help?

Please help us tackle plastic pollution today by giving a donation or joining up as a GCT member.

Related articles

New research shows that Galapagos giant tortoises are ingesting plastic waste

Creating a circular economy for plastics in Galapagos