How the global problem of coral bleaching is impacting Galapagos

Coral bleaching has become something of a nightmarish litmus test for the rise in global sea temperatures.

The reefs around Galapagos have not been immune from this phenomenon, and many scientists are now saying that what is happening in Galapagos could be seen as a model for the world’s oceans in years to come. Could Galapagos be a smoking gun for climate change? Or are we underestimating coral’s resilience to fight back?

Coral in Galapagos

It was only in the mid-1970s that coral reefs were discovered in the waters of Galapagos, before this date, it was assumed that the ocean wasn’t suitable habitat. Understandably so; Galapagos is situated at the intersection of five major current confluences and sitting right on the equator makes this an unpredictable marine climate.

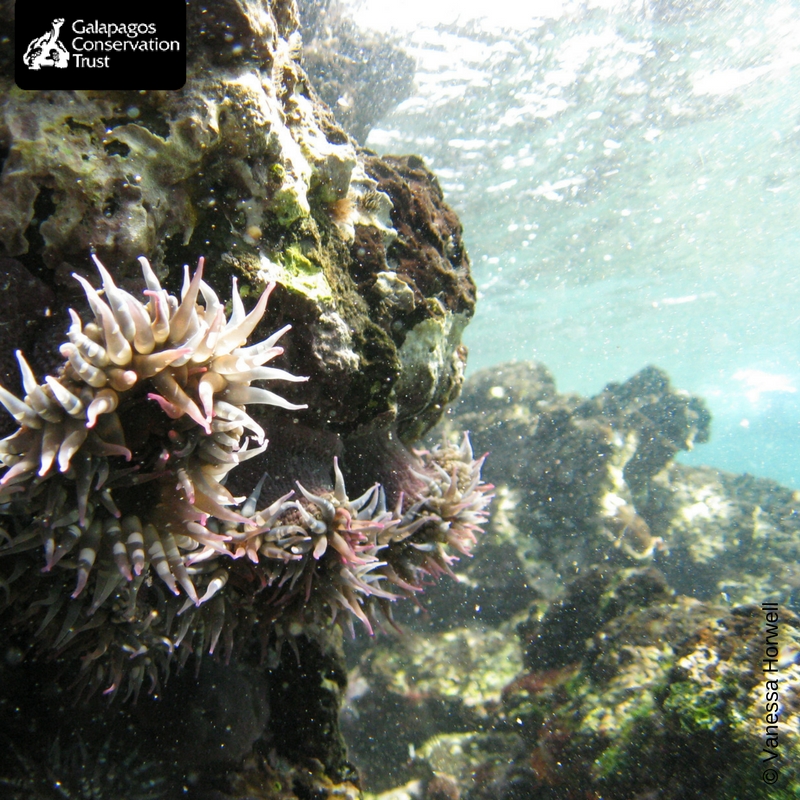

Corals are typically divided into two groups; those that contain zooxanthellae, the algae that live inside the tissues of the corals and provide the coral with food, and those that feed by stretching out minuscule tentacles to sting and catch zooplankton. It is the former group that form into what we call classic coral reefs. Unfortunately, it was not long after the initial discovery of these reefs in Galapagos that a major El Niño event occurred, in 1982-3, bringing extensive damage through bleaching to the little-known corals of Galapagos, severely restricting the team of researchers who had been monitoring them. Instead of being able to build a picture of the coral life of Galapagos they had to turn their attention to investigate the ability of the corals to recover.

Coral bleaching can occur when waters turn warmer. This is normally associated with particularly severe El Niño events and this has undoubtedly been going on for millennia. It happens because the corals are under stress from higher water temperatures, expelling the algae that live inside them, which leaves the tissues bleached white. Corals can, and do, recover but only if the conditions are suitable and the rise in temperatures is not prolonged. It was discovered that the coral around the southern waters of Galapagos found it harder to recover than those further north, due to high levels of carbon dioxide, another issue in the bleaching story. Higher carbon dioxide results in greater acidity as it affects the reefs, disrupting the coral’s ability to create calcium carbonate which is the building block of their hard structure.

Coral and anenome © Vanessa Horwell

However, following a second major El Niño event in 1997-98, a team of scientists led by Professor Terry Dawson of Southampton University discovered that the corals in the northern section of the Islands were recovering well. In fact, they discovered three new coral species that were previously thought to have been absent in Galapagos waters. Certain species of coral seem to have a tolerance to rises in temperature within a certain temperature span, so could what the scientists are seeing in the differences between the southern and northern ranges of the Archipelago be a model for what might occur globally in the next 30-50 years?

Although reversing the trends of climate change is a huge undertaking that no single organisation can overcome, we at the Galapagos Conservation Trust are doing our bit to help preserve the Enchanted Isles with your help. Many of the projects we support aim to secure funding to carry out vital baseline research to help build a picture of the marine ecosystem in its entirety. For example, we fund the globally significant Galapagos Whale Shark Project, to assess the abundance of marine megafauna. The presence or absence of key indicator species such as whale sharks gives us a good insight into the overall health of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, including the fragile corals.

Please help us continue to fund crucial marine projects in Galapagos by donating or joining GCT.

Related articles

Climate change and plastic pollution: the inextricable link

Santa Cruz: The Evolution of the Agricultural Zone